My niece asked me for a story. It was a hot summer afternoon, and she was bored with her toys and her books and her game screen. What kind of story, I asked. A story about heroes, she said. You mean, like the boy who killed the bear who had three heads, or the girl who returned the moon to the sky? No, no, my niece said. Not made-up stories. A for-true story. So, I asked, like about doctors or firefighters or folks who jump into rivers to save people who don’t know how to swim? No, no, no, she said, looking at me in the way that four-year-olds do when they can’t believe how dense you are being. A story with you and my daddy in it.

My niece asked me for a story. It was a hot summer afternoon, and she was bored with her toys and her books and her game screen. What kind of story, I asked. A story about heroes, she said. You mean, like the boy who killed the bear who had three heads, or the girl who returned the moon to the sky? No, no, my niece said. Not made-up stories. A for-true story. So, I asked, like about doctors or firefighters or folks who jump into rivers to save people who don’t know how to swim? No, no, no, she said, looking at me in the way that four-year-olds do when they can’t believe how dense you are being. A story with you and my daddy in it.

I bought some time by pouring us both lemonade, and then fiddling with the fan for a bit. Well, I said, I can’t honestly say I ever knew any heroes personally. You’ll have to ask your daddy if he knows any stories like that, when he gets home. But I can tell you a story about a person who set an example. Will that do?

I guess, she said, after a moment, though she looked skeptical.

All right then.

There are people you have to say hello to, even if you don’t want to. Your grandmother taught me that. In the city, she said, people passed each other without a word, a smile, or a nod, and nobody knew their neighbors’ names. But that is not the way we acted in Brimeden.

Brimeden is a village, though it calls itself a town, and in a village everybody knows everybody else. This does not mean everybody likes everybody else. There were plenty of people in Brimeden that my mother could not stand. But on the street or in a shop, my mother would say Good morning, or Good afternoon, or Nice weather, isn’t it, to people who voted against her for the school board, or whose dog kept us awake with its barking night after night. My mother had very rigid ideas concerning proper behavior.

Yes, you’ve been to Brimeden. You don’t remember because you were only eight months old. Your daddy took you for your naming ceremony. No, your grandmother wasn’t there. You know she died the winter the trees walked. That’s one good thing about living in the city. They keep the trees in cages here. But you saw the woman I’m going to tell you about, and she saw you, though she didn’t say hello, or smile, or nod.

Her name was Lulka, and she’d been born in Brimeden, had grown up there, and never once left it, as far as I know. She still lives there, because if she had died, I’m sure a dozen or two people would have messaged me, to say Whew, finally. You see, nobody in Brimeden liked her. Nobody at all.

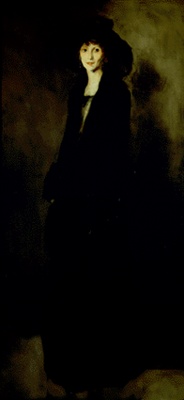

She was a tall woman, a little stoop-shouldered, and always dressed like she’d been invited to a formal party, even if she were just walking up to the corner store for some milk. And she never spoke to anybody, and never smiled. Never even looked at you, if she could help it.

Mean? I don’t know if I’d say she was mean. She was’¦indifferent. Do you know that word? It’s like when you don’t care one way or the other. Imagine it was raining right now, and you had to cross the city on foot. If you had an umbrella, would that make you happier than if you didn’t have an umbrella? Right. If it didn’t, that would make you indifferent to the rain. Lulka was like that. She was indifferent to people.

Like’¦ suppose you were playing outside her house, and you fell down and hurt yourself. She wouldn’t care, you see. She wouldn’t push you and make you fall, but she wouldn’t come out to make sure you were all right if you did. Do you understand what I’m saying?

Yes, she was that way with everybody. Kiddies, grown folks, animal beings, plant beings, passing beings.

No, she never got invited to parties.

No, she never said hello to anybody.

I told you this wasn’t a story about a hero. It’s a story about someone who set an example.

Do you remember a couple of months ago, when spring was coming, and the municipal societies held those parades and street fairs, and all that stuff? Right, you got to ride on a real live horse. They do that sort of thing in the city, because magic doesn’t visit here. So we have festivals instead.

In Brimeden, at the turn of every season, a little bit of magic dropped by. It didn’t stay long, and if no one noticed it, it vanished again. Folks kept their eyes awake, but many times it happened that season-turn came and went, and not a single person caught a glimpse or a touch of anything other than the ordinary articles of the six-sided world. You know why people say, See a pin and pick it up? That’s because magic always comes in disguise.

Good magic, I mean. The kind for luck, and love, and health, and success. Sure, it could look like a pin. Could look like a leaf, too, or a stone, or a bent spoon, or a button, or an old sock. Socks were best, people used to say.

No, I never found one. Truth to tell, I never looked too hard. You see, where your grandmother and grandfather and your daddy and I used to live, it wasn’t one of the places the magic showed up. There were only four or five spots like that in Brimeden, and every one of those spots was claimed by the family that had first steaded it, even if they didn’t live there anymore. So when each season-turn came, those folks camped out on those spots, with blankets if it was cold, tents, even. Of course you didn’t have to do that in summer. Then it was the flies and the gnats and the mosquitoes you had to worry about. Plenty of folks that weren’t family, not even by marriage, or adoption, or neighbor-kin bond, showed up, too. Sometimes there were fights, but mostly people kept quiet and just glared at each other, because they were afraid they would miss the magic when it came.

Finders keepers? Yes, it was like that. But suppose we went into your room right now, and there was a twenty-cent piece on the floor, and you saw it first. But I was faster than you and snatched it up, and said it was mine. Right, I don’t think that would be fair, either. But there’d be nothing you could do about it. You’d tell your daddy? Okay. In Brimeden it happened that sometimes folks went to law. To court, you understand? Let me tell you, that just made more mess.

Well, this one time, the magic fooled everybody. Magic will do that—play tricks. It came a day early. And guess who found it?

You got it. Lulka. It was the day before spring, and she was coming back from her marketing, with a basket over her arm and her fine clothes and her shut-in face, and there it was on the pavement right in front of her, a little blue ring that wouldn’t hardly fit a baby’s pinky finger. She stopped, of course. She stopped and she looked at it. And then other people stopped to see what she was looking at, and before you knew it, half the village was there. Nobody, though, sent a runner to tell the family with a claim on that stretch of pavement. You didn’t message about that sort of thing, back then. It was sort of a superstition. Word had to pass from mouth to mouth, otherwise it would be bad luck. Anyway, the folks who first lived on that street, back when it was only shacks and outhouses and not stores and pastry shops and a lawyer’s office, had moved all the way to the other side of Brimeden, to a big house on the hill with a view of the river. They were the last of all to find out what happened that day.

“Go on,” somebody said to Lulka. And the crowd, which up till then had been pretty quiet as crowds go, started muttering and stamping their feet, nudging each other and passing remarks.

Yes, I was there. When I saw the crowd gathering, I went to see what was going on. I saw the little blue ring lying there on the sidewalk with my very eyes.

No, your daddy wasn’t there that day. This happened in the afternoon. He was still in school then.

“Good afternoon, Ma’am Lulka,” I said, because your grandmother always said that when she saw her, and she made me say it, too, if I was with her.

Lulka didn’t answer me. She didn’t answer the man who’d called out, “Go on,” either. She just stood there with her basket on her arm, looking at the little piece of magic.

It could have been health. It could have been long life. It could have been one of those things that always kept your pantry full, or did your cleaning for you. It could be that if you put it up to your eye, you could see the future, or little bits of it, anyway. Maybe if you hung it around your neck, you’d be able to fly. Maybe it was a wish ring, and Lulka could have wished for everybody in the village to love her.

No, we never found out.

Someone else, not the first man, shouted, “Pick it up!”

Lulka didn’t look at anybody. She said, firmly, “It’s not mine.”

The crowd got quiet then. Very quiet, like they were all thinking hard.

Lulka looked at the piece of magic for another minute or two, then walked around it and continued down the street toward her house.

The crowd didn’t move. For a little tiny stretch of forever, not a person even shifted their feet.

Then they all made a dash for the blue ring.

I don’t know who got it. Somebody did, that’s for sure. But whoever it was kept it hidden, never told anybody he or she had it, and never spoke about what the piece of magic could do.

But see, for a while there, Lulka set all those folks an example. It didn’t last long, but then most things don’t last very long. You’ll find that out for yourself when you get older.

She did the right thing. It didn’t make people like her any more. Made them like her less, to speak true. But I don’t suppose Lulka cared, one way or the other.

After that, every time I saw her, whether your grandmother was with me or not, I said hello to Ma’am Lulka. She never said hello back. Never nodded, never smiled. But I didn’t say hello to her to get a greeting back. I didn’t do it for her. I did it for me.

I left Brimeden a couple of years later. I like the city better. There’s no magic here, that’s true. But magic isn’t the most important thing in the world. Never let anybody tell you it is.

Yes, your grandmother set an example, too. Oh, loads of them. Ask your daddy, he can tell you a hundred stories. But the example I remember most is the one I learned from Ma’am Lulka. You might not believe this, but it comes back to my mind nearly every day.

I think it’s time to start tidying up the kitchen now, don’t you? Thank you, sweetie, yes, put the glasses in the sink. Now, what do you want for supper?

Patricia Russo‘s stories have appeared in Fantasy, Lone Star Stories, Talebones, Tales of the Unanticipated, Abyss and Apex, Not One of Us, and a lot of other places. She won’t talk about cats or hobbies, because she has neither.

IMAGE: Lady in Black Velvet, Eulabee Dix, 1911.