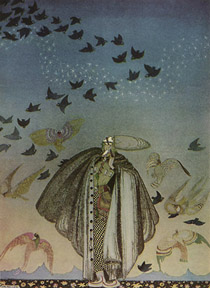

There was once a queen and she had a little daughter, who was as yet a babe in arms; and once the child was so restless that the mother could get no peace, do what she would; so she lost patience, and seeing a flight of ravens pass over the castle she opened the window and said to her child, ‘˜Oh, that thou wert a raven and couldst fly away, that I might be at peace.’ (Brothers Grimm)

She changed almost immediately, sprang from my arms into the living room window, clattered at the glass with beak and claws as she tried desperately to make her wings work.

She changed almost immediately, sprang from my arms into the living room window, clattered at the glass with beak and claws as she tried desperately to make her wings work.

I watched her watch the flock of ravens as they flew out of sight, over the terraced roofs, chasing wind torn scrags of cloud.

I was still holding my arms as though to cradle her and support her head. She shifted on the windowsill, tried to extend her wings and began to cry. Not the shrieking mewl that had been piercing me for weeks but a raw caw-cawing sound.

I sat down on the floor. She perched on the edge of the windowsill, claws digging into the paintwork, and turned to face me, head cocked to one side, her blue eyes darker, black feathers shining in the thin winter sunlight. She clicked her beak.

I wondered if I should shut the window in case she tried to fly again, but she didn’t move. Neither did I.

I looked at the washing basket on the floor beneath the window, heaped with clean babygros, blankets, and sheets that needed sorting and putting away. In the corner of the room was the moses basket I tried to get her to sleep in during the day. I knew an unsucked dummy lay on the yellow sheet, beside where her head should have been.

She clicked her beak again, then stretched her wings. Already so big, surely she should have become a baby raven, or was this what baby ravens looked like?

We each sat and watched the other. It was starting to get dark. I should have put the lamp on, but I didn’t move. She was quiet now. The streetlights clicked on outside and her feathers looked even blacker against their orange glow. I couldn’t see her eyes. Tony would be home soon. I didn’t know what he was going to say.

She shifted from foot to foot then stretched her wings again. She jumped a little. She was going to try to fly. I imagined her crashing towards me. Her beak aimed at my eyes. I clenched them shut. There was a clatter. I opened them and for a moment I had no sense of where she was in the room. I looked at the empty windowsill and up at the open window. Then I heard her beak clicking. She was perched on top of the baby gym. I’d told Tony that she didn’t need it up yet, still too young, it was just clutter, but he’d put it up anyway.

She gripped the orange plastic and experimented with bobbing her head down till she could bat the assortment of jingling animals. As she got more confident she managed to knock a button on one and a grating, echoey version of ‘˜Twinkle Twinkle’ began to play. She paused to listen, then knocked the button again.

I shifted my weight to get up. She didn’t notice. She was too preoccupied with her toy. My legs had gone numb. I struggled to stand and gripped the settee as I waited for the pins and needles to surge through them. I stumbled to the lamp and switched it on. It made her jump. She landed on the floor and stared up at me. Started to click her beak again.

I wondered if she might be hungry. I didn’t know what ravens ate. All we had in was a freezer full of microwave meals and a packet of Jammy Dodgers. I went to get her a jammy dodger. I took longer over opening the biscuit tin than I should have. It was brighter in the kitchen. I knew she hadn’t flown out of the window. I could still hear ‘˜Twinkle Twinkle’ grating on and on.

I took the biscuit in to her and put it on the floor, as close as I dared get. She jumped down, nudged it with her beak, looked at me, went back to the biscuit, pushed it a little way across the carpet then looked at me again. She cawed. She hopped towards me. She was looking at my chest.

I started to get the idea. I’d always said there was no way I was breastfeeding her once she got teeth. I’d hadn’t expected a beak. I shook my head and backed away towards the door, back towards the brightness of the kitchen light. She cawed again. I remembered the breast pump that was still in its packaging on top of the freezer. It had looked too fiddly. I’d been too tired to work out how to use it. The box said you had to sterilise every part of it, and we hadn’t bought a steriliser because I was breastfeeding.

She cawed again. I went and got the box.

Sitting on the settee I tore off the plastic wrapping and pulled the various plastic implements out. We’d have to do without sterilising. A raven was different to a baby anyway. I followed the instructions to construct it. In the ‘˜top tips’ it said you had to relax to be able to express milk. She cawed and hopped to my feet. I held one arm out so I could bat her away if she launched at me. She cried out; it sounded more like her old cry. I pulled my swollen left breast from my bra and milk began to spray out, doing half the job for me. I attached the sucker end and began to pump the handle. It hurt. I watched her watching me.

I couldn’t give it her in the bottle that I’d pumped it into. I went to get a saucer, her claws scrabbled on the laminate dining room floor; she was following me. I didn’t look down, just went straight back into the living room and placed the saucer of thin off-white milk on the floor. She dipped her beak into it and extended a thin black tongue. She made a strange rattling sound as she drank.

Sated she burped. Something I’d never been able to get her to do after a feed. She stretched her wings one last time before curling them back into herself where they became arms.

She was a baby lying on her rug when Tony came in. ‘˜Great,’ he said, ‘˜you managed to figure out the pump.’

I closed my eyes and slept.

![]()

She’s three now. Bright and troubling. She hides things, steals things, eats worms. People tell me all three year olds do those things, but do they?

Her eyes have changed from greyish blue to brown. In the morning I find black feathers on her pillow amongst the fine blonde hairs she’s shed in the night.

But we play, and the days go quicker than they did. Most days I don’t worry about her too much, until we get to the playground. I see her at the top of the climbing frame’”arms outstretched’”and I wonder how long it will be before she tries to fly.

Claire Massey lives in Lancashire, UK with her husband and two young sons. Her short stories, poetry and articles have been published in a variety of magazines both online and in print including Flax, Enchanted Conversation, Rainy City Stories, Literary Mama, Magpie Magazine, and Brittle Star. She’s also had a short play produced at the Contact Theatre in Manchester. Claire is the founder and editor of online magazine New Fairy Tales and she blogs about fairy tales at The Fairy Tale Cupboard.

IMAGE: A Large Flock of Birds, Kay Nielsen

Quote from: Grimm, J. & Grimm, W. Translated by Crane, L. (1993) Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Ware: Wordsworth Editions