This past March, I had the pleasure of attending the Myths and Fairy Tales in Film and Literature post-1900 conference at the University of York. As well as being a sort of CdF reunion, with Helen Pilinovksy and I seeing each other in person for the first time in several years, I had the opportunity to meet one of SB’s authors, John Patrick Pazdziora, who as well as being the author of some fantastic fiction and poetry, is a doctoral candidate at the University of St. Andrews. John, along with Catriona McAra and Emily Dezurick-Badran, presented papers for the Anti-tales panel.

Having seen references to the term anti-tale in passing prior to this event, my curiosity was piqued by this seemingly new way of looking at story, especially–but not only–as it applies to fairy tales. So, in between panels, I asked John if he would mind answering a few questions about the anti-tale for the readers of CdF. He was happy to oblige.

CdF: Tell us something about the history of “anti-tale” and what it means for scholarship today.

JPP: Before I get into answering this, I need to acknowledge the tremendous debt of knowledge everyone working on anti-tale owes to David Calvin (Univeristy of Ulster) and Catriona McAra (University of Glasgow).

David is primarily responsible for the revival of “anti-tale” as a critical term. He’s done some simply outstanding work on postmodern fairy tales, and his research has set a course for the rest of us to follow. Catriona, in her collaboration with David, has broadened out anti-tale into an interdisciplinary and multi-modal expression through her study of surrealism. She’s worked tirelessly both in arranging the anti-tale conference in Glasgow last August, and in orchestrating a striking array of critical expertise for the anthology, Anti-Tales: The Uses of Disenchantment (Cambridge Scholars, 2011). In all honestly, everything I’ve learned about anti-tales, I’ve learned from them. They’re outstanding scholars. And they’re both really wonderful, fun people too. So it’s my privilege to have them as colleagues and friends.

They’re probably going to murder me when they read that, but oh well.

I say all that because, to answer this question, I’m really just reiterating David Calvin’s research. Anti-tale as a term first appeared in the early 20th century as a genre marker–Anti-märchen as distinguished from Kinder-märchen, Wunder-märchen, and so on. Various scholars have used the term since, notably with reference to Kafka and authors like that, but not given it much more than a mention. David Calvin rediscovered the term, and recognized its relevance to the postmodern context–the sorts of deconstructive fairy tale retelling we’ve been seeing at least since the 70s. Again, as a genre marker, it’s been very useful in providing an umbrella term over subversive currents in the arts, and fairy tale scholarship in particular. Angela Carter, for instance, and her ‘demythologising’ project are in some ways a lodestone for understanding anti-tale–a good introduction, as it were.

The primary scholastic value so far has been retrospective, really. We have this term now, and people are talking about it and thinking about it. And it lets us look back at literature and the arts–at something like Waiting for Godot, say, which in many ways is the ideal anti-tale, or Tristram Shandy, or more recently Roald Dahl and Jan Å vankmajer–and say, ‘Oh, that’s what this is.’ It’s recognizing the shadow, really–recognizing it and naming it, instead of hedging around it with vague adjectives. Anti-tale is a shadow-genre; to invoke Jung, anti-tale is the shadow self of narrative–obscured, suppressed, and occluded voices and variants. Anti-tale scholarship provides us with a way of listening to those voices, of learning from them and beginning to understand them. Anti-tale is at its heart the voice of the Other, and the Outcast. And we need that. We need to hear those voices and learn from them.

I’m getting increasingly interested in the forward-reaching implications of anti-tale. What sort of critical theory will emerge from the genre study? What sorts of stories will be written, what sort of art created, if we’re consciously creating anti-tales? In many ways, it’s too early to say, but it’s exciting to speculate. And it will be exciting to see where the field goes. I’ve seen a lot of people, particularly emerging researchers and artists, getting very interested in anti-tale. It’s a very fertile concept, really. It holds a lot of promise.

CdF: OK, so let’s talk about this in terms of retelling original tales. Are retellings always anti-tales? If not, what is the difference between them? What markers can one look for in a story that would indicate that it is an anti-tale as opposed to a retelling?

JPP: No. Retellings are not always anti-tales. And anti-tales are not always retellings.

I think the classic examples of this are the Disney fairy tale films. There’s nothing ‘anti’ about them, at least not in the sense that we’re talking about here. Jack Zipes has been zealous in pointing out that they simply regurgitate the bourgeois and bowdlerized project of the Grimms and other late-Victorian popular collections. They perpetrate and exacerbate the existing variants. Now, that’s an example of it being done poorly, because it’s the negative elements–the objectification of women, and so on–that are getting preserved in these retellings.

You can, of course, get good retellings –where it’s the same tale simply being re-appropriated by a new teller. A good brilliant example of this is Padraic Colum, and what he does with ‘The Twelve Swans,’ transposing it into the Unique Tale in The King of Ireland’s Son (1916). That’s perhaps the single greatest retelling I’ve ever read, actually. Another outstanding brilliant example is the work Anthony Minghella did for Jim Henson’s The Storyteller (1987/1988). He took the existing tales and simply told them himself–not bowdlerizing at all, not trivializing at all, just reimagining and recapturing the mythic centre of the tale in a new linguistic form. Gorgeous.

In a way, it’s what a jazz or folk musician does with a melody. They learn the tune, the standard, but then make it their own. Each performance is uniquely different and uniquely theirs. That doesn’t make it any less the standard; that doesn’t make it any less available to any other musician. But the melody exists to be replayed and reinterpreted in that way. Fairy tales are like music, after all. They exist to be performed, to be spoken or sung. We tend to forget that. So that’s what retelling is. It’s improvising on a standard tale.

So, as I see it, a retelling preserves an ongoing tradition of tale and tale-telling. It’s a folk tradition, a performing art. An anti-tale, however, is destructive. It’s calling this process into question; it’s unwriting and untelling the tales. The Bloody Chamber, for instance, is an anti-tale in that it’s Bluebeard who gets blasted to hell by the heroine’s mum. But in that way it’s also a degree of wish-fulfillment, because a lots of mums probably would want to do something like that, if some guy was doing this to their daughter. So an anti-tale is an extreme reappropriation–it’s a tearing apart of the fabric of a tale to make one that we like better. Or one that challenges or hurts us more–one that makes us ask harder questions.

It’s not just improvising. It’s like what Arnold Schoenberg did, for instance–overturning not just the melodies of the masters, but the entire tonal structure of Western Music. Or Picasso, distorting the human figure, fracturing realism. That’s why so many anti-tale studies focus on the surrealists, actually–there’s a blurring and distorting effect of anti-tale that artists like these sought to capture.

An anti-tale doesn’t need to be the deconstruction of a particular tale. It can the dismantling of a whole tale-telling tradition–although you have to be very, very good if you’re going to do that. It’s not a coincidence that I mentioned Picasso! You need to be superb at the craft, to know the tradition you’re dismantling, before you can do it effectively. Otherwise you just get angry postmodernists writing very postmodern tales who think they’re being edgy. Well, they’re not. They’re just dog-paddling along behind Nabokov and Angela Carter. They’re dissing 1950s morality, sure, but we don’t live in the 1950s anymore. Elvis is probably dead.

For an anti-tale to be truly superb, it needs to be not only subverting a tale or a tradition, it needs to subvert the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age, the tales that are being told in the present and the immediate.

That’s what I’d say to look for, actually. Katherine Langrish wrote a wonderful article arguing that the very, very old, traditional tale ‘Mr Fox’ is actually a more effective and more liberating anti-tale than The Bloody Chamber. And I think she’s absolutely right. The term may be new, but anti-tales are as old as tales themselves.

And we shouldn’t assume a binary distinction–tales queue up on the right, anti-tales on the left, thank you very much ladies and gentlemen, don’t shove please, you’ve got all day to see Santa Claus! It’s not binary. It’s a continuum. There’s elements of tale and anti-tale in every narrative, I think. Like self and shadow-self, to use Jungian terms again. They’re both always present; they’re part of the same thing. It’s just a question of where on the continuum a particular tale or telling happens to fall. There’s nothing new to what we’re doing; it’s an old and a wonderful part of the old, wonderful tradition of tale-telling. If we’re missing that, we’re deluding ourselves. And we’re probably not telling very good tales, anti or otherwise.

CdF: It strikes me that the most powerful anti-tale might be one in which the author did not set out to write an anti-tale. You mentioned the surrealists, and I’m reminded of one of my favorite stories by Leonora Carrington, The Oval Lady. It contains some of Carrington’s usual motifs (the white horse, the number seven), which puts one on familiar ground, but in it she defies everything we know about story. I suspect ‘The Oval Lady’ (one story in the collection The Oval Lady) might be considered an anti-tale. Can you share with us some more recent examples of anti-tales, particularly fairy tales?

JPP: I think until recently you’d almost have to be unwittingly writing an anti-tale. You might be consciously writing a fairy tale subversion or a deconstruction, but the term anti-tale has only recently started to come into currency. I think we’ll start seeing more people trying to write deliberate anti-tales because of that, but you’re right–that does nothing to guarantee the quality.

Carrington isn’t an author I’m familiar with, but from your description it definitely sounds like a good anti-tale. For more modern examples–my chapter in Anti-Tales is on James Thurber’s Fables for Our Time (1940). That’s an excellent example. I just recommend Thurber in general. Also, Roald Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes (1982)–Cinderella marrying a jam-maker of good reputation–it’s incredibly subversive, and in keeping with Dahl’s political project. A man’s a man for a’ that, kind of thing. Samuel Beckett is a bit less recent, but most of what he wrote could be considered anti-tale, I’d say. Also Neil Gaiman, some of his stories in M is for Magic. And of course Kafka is the classic example.

These are all men , aren’t they? That probably says less about anti-tale than it does about me as a reader–but Angela Carter and A. S. Byatt are acknowledged as being luminaries of the genre. Margaret Atwood, too, with her fairy tale subversions. And, if you want something darker and weirder, Rikki Ducornet. And if we can step away from writing for a minute, Robert Powell and Tessa Farmer are two amazing young artists who are creating tremendous and deeply, deeply disturbing visual anti-tales. So, watch for their names.

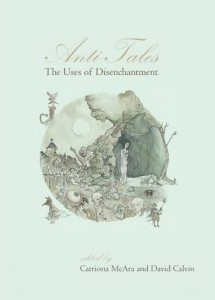

All of these authors, I’ll shamelessly add, are discussed in the Anti-Tales book that’s just been published. Robert Powell drew the cover for us, so it’s a little troubling. It looks like it was illustrated by the ghost of Hieronymous Bosch. That’s what did happen, actually–his ghost began haunting us with horrible doodles until we let it draw the cover. No, not really. We didn’t need a ghost this time. We had Robert, which was just as good. Maybe better.

CdF: Allow me to play the part of the skeptic for a moment. Why do we need yet another way of thinking about story? I understand that considering the anti-properties of a tale can lead to further elucidation and understanding of tales already told, but how does this further the craft of story-telling itself?

JPP: Stories are endless. We’ve not gotten to the bottom of them yet, and we never will. That’s part of what makes them so endlessly fascinating. How long does it take to read a story, to hear a story? Twenty minutes? Ten? But we keep going back to them and the best stories–like with all art–show us more and more and take us further and further every time. It’s like falling in love. Why do we scribble yet another love note that, if we face up to it, is exactly like every other love note we’ve written and says all the same things notes of that sort usually say? In the same ways? Because just one can’t say it all. We’re constantly trying to find words to say what we feel, to articulate our emotions, but we keep feeling even as we’re talking, so we need to keep talking. And it’s like that with stories.

As far as criticism–literary criticism is like science. We keep making new discoveries, we just don’t get on the BBC or Discovery Channel, more’s the pity. A hundred years ago, no one knew about DNA, no one knew about quantum, no one knew about relativity. They were all there, but it took a change of presupposition and a development of technology to bring them into focus. Anti-tale has been around since the beginning of tales–telling a story to a child, for instance, reading a familiar story, and you get this impulse to tease the child: ‘And the Big Bad Wolf ran into the house on a GIANT BULLDOZER and smashed through the brick and ate the three little pigs all up, nom nom nom warra warra!’ And the child is laughing her head off and trying to take the book away from you and wailing ‘Read it right! Read it right!’ That’s anti-tale. That’s what anti-tale really is. (Or maybe that’s just me, and my weird sense of humor when I read to children. I don’t know.)

We make it more complex and much darker, the way there are more complex and much darker stories than ‘The Three Little Pigs’; it’s like any art in that it has various levels, various stages of rarefication. But anti-tale begins with that–with a very human desire to ask, what happens if things turned out differently? If we take this apart and turn this upside down,? If we look under this rock or inside this cave? It’s a very human desire to explore, to change, to turn things upside down. We do that with everything, and we do that with stories.

How does it help us with story-crafting, well–it helps to know what we’re doing. The more you know about stories, and the more you know how stories work, the better your stories will be. Any great author is also a great reader; writing has been traditionally very much a folk tradition in that way. You learn folk music by going out and listening to folk music. You learn to write by reading great writers. It’s no substitute for natural genius, and I’m not downplaying that, but even a natural genius learns from their tradition, of music or painting or writing or whatever.

Where writing has fallen behind the other arts is in the theory of it. There’s an elaborate and very sophisticated musical theory, for instance, which isn’t interpretative but is just recognition that in Western music, these chords related to other chords in a certain way, and these forms can be used to build these structures. So you have terms like sub-dominant and antiphonal and counterpunctal–it’s a description of techniques, of what the masters have done and how we’ve observed that stuff works. That’s not a value judgement, it’s just observation of a craft.

Writing has just as much complexity, we just haven’t classified it. It’s haphazard. So I think, for writers and storytellers, anti-tale can be a step toward that sort of observation, that level of understanding. It helps us understand not only what we can do, but what other writers and tellers have done. You can never understand too much about your art. I don’t care what the art is–you can never understand it too much. The more you learn, I think, the more you enjoy it.

And story, as I said, is endless. We could learn forever and never learn everything. Anti-tale is a part of that. Now we’ve seen it, we can ask questions of it and learn more and more about it, and then create new anti-tale and anti-anti-tales that give us even more to think about and learn. And to read and to enjoy, which is really the whole point.

So that’s what anti-tale is, and why I think it’s important. It’s an exciting discovery to be a part of.

CdF: Indeed, if we didn’t keep revisiting certain stories, this website would not exist. I get the feeling we’ve barely scratched the surface here of what the anti-tale means for past and future literature and the arts. That, for me, makes it all the more exciting. Thank you, John, for sharing your time with us!

If anyone is interested in reading more about the anti-tale, the anthology mentioned above is available for purchase:

Anti-Tales: The Uses of Disenchantment

Anti-Tales: The Uses of Disenchantment

Editor: Catriona McAra and David Calvin

Date Of Publication: May 2011

“Although anti-tales abound in contemporary art and popular culture, the term has been used sporadically in scholarship without being developed or defined. While it is clear that the aesthetics of postmodernism have provided fertile creative grounds for this tradition, the anti-tale is not just a postmodern phenomenon; rather, the “postmodern fairy tale” is only part of the picture. Broadly interdisciplinary in scope, this collection of twenty-two essays and artwork explores various manifestations of the anti-tale, from the ancient to the modern including romanticism, realism and surrealism along the way.”

John Patrick Pazdziora is a freelance writer, editor, and critic. He’s also a doctoral candidate at the School of English, University of St Andrews, so that just proves he’s mad. He writes almost anything he can at nearly every opportunity, including lyrics and academic essays. But his first true love is fantasy and fairytale.