Legends from Fairyland

Harriet Parr, writing as Holme Lee

Reviewed by Elwin Cotman

Some people speak of books as treasures. I find this to be true. Reading a book offers a door into the author’s imagination. The better the writer, the better the journey. This kind of bond between writer and reader is certainly something to cherish. However, every once in a while you find a book that literally feels like a treasure. Something about the age of the book, the prose, the design that no one uses anymore. One such book, to me, is Holme Lee’s Legends from Fairyland, a long-forgotten classic, one of the great fairy tales of the last two hundred years.

Some people speak of books as treasures. I find this to be true. Reading a book offers a door into the author’s imagination. The better the writer, the better the journey. This kind of bond between writer and reader is certainly something to cherish. However, every once in a while you find a book that literally feels like a treasure. Something about the age of the book, the prose, the design that no one uses anymore. One such book, to me, is Holme Lee’s Legends from Fairyland, a long-forgotten classic, one of the great fairy tales of the last two hundred years.

If any place on Earth screams “You will find treasures here!”, it is a second-hand book shop. The dusty smell, the shelves packed from floor to light fixtures with fraying tomes, the idea that the intrepid reader could unearth a priceless antique. The historicity of the books themselves; the library cards in the back from the early 20th century; the Christmas or birthday notes in the frontispiece, the gift-giver and receiver probably long dead. Just walking into such a store makes me feel like an archaeologist.

One such place, for me, was in Eastland Mall. Pittsburghers will know this place: the dead mall in North Versailles, now torn down and replaced with an ugly cement slab behind a fence. Even when I was a kid, the mall was in its death-throes. It had the weekend Superflea where you could drown in pop culture. There was the driving school on one side, a few scattered shops, a rotting movie theatre in the corner of the parking lot, bubblegum machines with stale gumballs hard as concrete. Needless to say, a place like this had its own magical qualities. I had fun exploring the abandoned office space, parting plastic sheets to drift from room to empty room. Whenever we visited the Superflea, my father also took me to the single room book shop. It felt appropriate: a store of myths, right next to the cultural blender of the Superflea, in a dying temple of commerce.

In the bookstore, I discovered the Knights of the Round Table and the Thousand and One Arabian Nights. Old-style children’s editions, printed on glossy paper, with color plates of Merlin getting tricked by Nimue or the Forty Thieves hiding in oil baskets. In this place of wonder, I found Holme Lee’s Fairyland.

The child I was must have thought I’d unearthed an actual manuscript about, or from, a fairy civilization. It was unlike anything I had ever seen. There was no way, in looking at this book, I could have avoided Neverending Story-type fantasies. Fairies filled every available space. Elves and cherubs crowded the full-page drawings, observing the main action from branches and flowers. Sprites flew, danced and strutted through the margins. They clung to the vines along the initial letters. There was not an inch of paper that a fairy didn’t claim as their own, looking at the text as if reading the story themselves. No human could have made this, I must have thought. It had to be a gift from the sidhe.

What I in fact held was the 1988 Crescent Books hardcover edition of Legends from Fairyland, written by Holme Lee, copiously illustrated by Reginald and Horace Knowles. Even as an adult, the book held an air of mystery for me because, until recently, I could find so little information on the creators. Who is Holme Lee? Who is Effie H. Freemantle, who wrote the introduction and the short fairytale at the back titled “The Green Shoes”? Was Freemantle like “S. Morganstern” from The Princess Bride, a fictional editor created to add spice to the story? Is Freemantle a real person, or another facet of Lee?

“Holme Lee” was undeniably not a real person, being the pseudonym of Harriet Parr (1828-1900), a Victorian-era English writer. At the height of her success during the late 1800s she authored serials, short stories and hymns. She published pieces in Household Words and All the Year Round, and her stories were mostly drawing room dramas, which must have met the approval of the journals’ editor: Charles Dickens. Parr collaborated with Dickens on a number of his Christmas stories. Parr wrote Legends from Fairyland in 1860, and followed it with short stories about the explorer character Tuflongbo (who was apparently born in an apple core and traveled among the ogres). Fairyland proved so popular that subsequent stories of hers had “From the author of Legends from Fairyland” on the title page. In her time, Parr was best remembered for writing a biography on Joan of Arc. Despite being a pioneering female in a male-dominated industry, Parr’s work has evidently fallen into obscurity.

Reginald and Horace Knowles were early 20th century children’s illustrators. They made their illustrations for the 1908 edition of Fairyland, published by the J.B. Lippincott Company, and it is now impossible to imagine the book without their contribution. Their Art Nouvelle and Romantic-inspired work also appeared in Norse Fairy Tales, Old World Love-Stories and Peeps into Fairyland. There has been a recent resurgence of interest in their work, particularly in the business of greeting cards.

Freemantle was a real person, and could not have been Parr, since the edition she forwarded came out eight years after Parr’s death. It is almost impossible to find information on her. I do know that her intro to Fairyland is more twee than anything in the actual book, and the inclusion of her own story suggests coattail-riding was alive and well in 1908.

But what of the book itself?

The book is part star-crossed lovers story, part morality play, part quest, part ethnography of a land that never existed. The fairyland in reference is Sheneland, which is located somewhere on the edge of the human world (or the Country under the Sun) and always on the edge of Shadowland. Sheneland is very much a magical realm. This is a place where old moons are cut up to create stars, where fairy royalty travel in ships made from seashells while their retainers ride on bumblebees. This is a land where stealing eggs from robins’ nests is punishable by law, and coming between true love is punishable by death. Sheneland has its own history, geography (but don’t trust too much to maps), customs and laws. All of which makes sense, in a fairy tale way. People from the Country under the Sun can interact with fairies, but rarely do; Sheneland seems to exist in that unreachable realm of imagination and mystery. The book should be studied, if only as an early example of fantasy world-building.

Fairyland begins, as a story like this must, with all of Sheneland preparing for Prince Glee and Princess Trill’s upcoming marriage. The novel proceeds through various plots by Trill’s evil Aunt Spite to break up the lovers. This includes kidnapping Trill and imprisoning her in Castle Craft, spreading slander about Glee’s fidelity, and whisking Trill to the Land of the Giants. Many characters get caught up in the events. Not just fairies, but talking dogs, ghosts, and the insect-like people of the Aplepivi.

In fact, Fairyland has an extensive cast. There is the gallant Prince Glee and his true love Trill, who sings like a nightingale; Aunt Spite, whose claims of nobility are undermined by her evil nature; the blustery Tippet and his immature friend Wink, who spend their days gossiping in the shade of a toadstool; the Royal Society of Wiseacres, who make it their business to be curmudgeonly; Mischief, Spite’s unpredictable and treacherous daughter; the benevolent Fairy Queen; Worry, the head dog in Fairy Queen’s kennels; Professors Prize, Holiday, Treat and Jolly, the teachers every fairy child wants; Professors Birch, Twig, Cane and Ferule, the teachers they do not want; Tuflongbo, the loquacious but kind-hearted explorer; the Wicked Fairy of the Tree with Many Tendrils; Story, the Court Moralist; Old Woman, who takes the shine off dewdrops to spin gowns for the fairy ball. Obviously, Parr is dealing with broad characterizations. The majority of characters bear names that reflect their personalities, each in their own way demonstrating good and bad behavior to the novel’s young readers. Not only does Parr understand the way these tropes work, but she effectively weaves these many symbolic representations into an epic narrative.

The people of Sheneland seem to occupy their days with masquerades, weddings, spreading mischief and going on holiday. They are fairies, and making merry is what they do. However, like all good fairy tales, there is a real element of danger. Giants, unethical mask sellers, and the continued machinations of Aunt Spite all threaten harm. It is implied that, even though the fair folk are long-lived, they, too, must ultimately make the journey to Shadowland.

It is worth noting that, for all her symbolic nature, Aunt Spite is a well-rounded villainess. Possessed by an obsessive need to destroy her niece’s happiness, she jeopardizes her own safety time and again. It is implied that she was once welcome at Elfin Court, but a change in monarchs caused her to be a pariah. Everything she does stems from her deep-rooted need to feel accepted by the fairy aristocracy, something that will never happen for someone like her, leading her down an endless cycle of wicked stepmother schemes. Spite is a complex, even sympathetic villain, the kind rarely seen in children’s literature of that time.

Parr understands the essence of fairies: they are not just tiny people with wings, but symbolic of everything that is unknown and unexplainable. After all, narwhals were once thought to be mermaids, and giant lizards were once dragons. The language of mythology is the language of the obscure. Parr realizes this, and thus there is an air of mystery to her fairy world. This is illustrated in the chapter about the Solemn Festival of Midsummer’s Eve. Parr describes the moonlit procession of Elfin Court to the Enchanted Bower:

Torches are carried before them by the Gnomes who work in the Mines, to light the path which winds, and turns, and twists, through a bewildering labyrinth for miles and miles. The procession is made in perfect silence, and all the way as the fairies go they pluck flowers, weeds, herbs and branches; never pausing, never stooping, never speaking, and never looking either to the right hand or to the left. As they pass into the Enchanted Bower they cast them all down into one heap by the door, and then range themselves mutely around the garlanded walls, while Fairy Queen takes her seat on the Golden Throne in the midst.

All is so still that the chirp of the insects which wake by night in Elfinwood is heard like a chorus of music, mingled with the chiming of blue-bells and lily-bells in the moist and shadow places. Suddenly the inner gates of the Enchanted Bower open; and a cold breath blows softly through; then there is a sound as of trailing robes over crisp leaves in autumn, and then appears a misty figure whose face is covered with a veil. She moves like a shadow, diffusing all around her a chill air, and takes her place beside the heap of flowers, weeds, herbs and branches, which the fairies gathered by the way and flung down in a heap at the entrance of the Enchanted Bower.

As she comes forth, the Moon rises and the Stars twinkle out one by one; and just as the Fairy Bells chime midnight all Elfinwood echoes to the rush and hurry of light feet, -not fairy feet, but feet of maidens from the Country under the Sun, who, on Midsummer Eve, come out to Sheneland, to inquire of the Veiled Shadow of the Future what their fate shall be; and on this night, once in a year, she draws their lot, and shows it to them by the emblem of some flower, weed, herb or branch, which she lifts from the heap at her feet, and gives into their hands.

Though all of Elfin Court attends, none of them seem to know exactly what the Veiled Shadow of the Future is. They also do not question their role in this ritual, a solemn diversion from their normally joyful lives. They respect the Veiled Shadow of the Future, and perhaps even fear her. It is evident that the Shadow is neither good nor evil, but represents the capriciousness of fate. She is also connected to the earth, using plants for her fortune-telling. This is one of few points in the narrative where humans interact with fairies. Most of them receive fortunes that leave them in despair, so that maybe they would rather they did not know. Magic, with all of its unknowable qualities, is potentially devastating to humans. Nothing is explained, nothing is rationalized. Like the fairies, the Veiled Shadow of the Future simply is. Parr is working at the height of her lyrical skills, the paragraph-long sentences and repeated phrases looping upon themselves until the words hypnotize. In this passage, she hints at forces greater than the fairies, which humans could not possibly comprehend.

Parr’s overall writing style is witty and unpretentious; words in all capital letters and multiple exclamation points make an appearance. She makes liberal use of puns and sarcastic asides. Using simple, lyrical prose she conjures up scenes of fairies emerging from the lilies and moss to laugh at the foolish maid Idle; Tuflongbo leaping across an ocean in three strides; Giant Slouchback trotting along at three hundred and sixty-five miles an hour. It is this mix of minimalism and lyricism that perfectly captures a fairy tale feel. It also provides for subtle world-building. Characters are mentioned in passing before they appear in the narrative, and she drops hints of history to add depth to the world.

Most noteworthy is that Parr writes in colors. There are silver rays in dew, wild white roses, black puppies, ugly yellow smoke, pearl and pink sailing vessels, green fern dresses, the golden gates of the Sun Pavilion, the blue jerkins and scarlet stockings of Fairy Queen’s four-and-twenty page boys. Parr mines from the entire rainbow to detail her story, and it livens up the proceedings even when the plot is not moving forward.

The structure of the story is unique in that the main narrative does not go into effect until halfway through. A large section of the book is dedicated to world-building, done through the story’s chief device: the telling of legends.

A major drawing point of the novel is its stories. The book is stuffed full of them. Not just legends, but stories in general, anecdotes about weddings and tales of heroic deeds. As with our own society, tales are an intrinsic part of Sheneland culture. However, this culture is unique in that their legends are literally history. They are interspersed throughout the novel, utilized in different ways. There is “The Ugliest Cat in All Sheneland,” used as a moral to naughty young fairies. There is the State Traveler Tuflongbo’s journey to the end of the world, and his travels among the Aplepivi, narrated as a rousing tale by the explorer himself. The haunting tale of “The Enclosed Garden on the Borders of Sheneland Where the Sun Never Shines” is told as a warning to Aunt Spite. Towards the end, the story moves into Pilgrim’s Progress territory with “From Sheneland to Shadowland.” This is a book that often gets wonderfully sidetracked, giving the reader a clear picture of Sheneland. Only now that I am older do I see the significance of some of these tales.

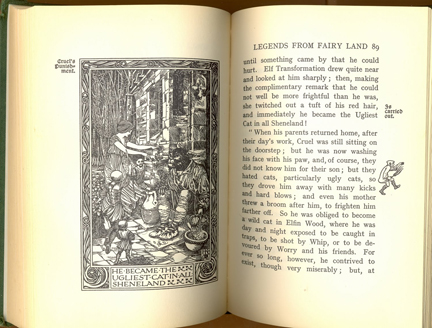

It is telling that Story, the Court Moralist, has a major role in the book, even if he does not have much screentime. Parr’s book is a traditional fairy tale in that a major theme is imparting values to youth. Story tells two of the legends in the novel, and both are used as warnings to bad fairies. The first is “The Ugliest Cat in All Sheneland,” a singularly violent tale in the Brothers Grimm tradition. In it, a boy named Cruel tortures animals and kills six innocent puppies in brutal ways. In turn, Elf Transformation changes him into the Ugliest Cat in All Sheneland, and he receives a karmic comeuppance. His behavior is punished, while the good children who tried to help the puppies are rewarded.

Story relates this legend in court, as a warning to the egg-snatching fairies Prig, Pickle and Slumph. His tale basically marks their last chance, and any subsequent wrongdoing will result in harsh punishment. In fairy society, as in ours, the judicial system is based off of traditional ideas of right and wrong. The inclusion of the legend as a part of the judicial and rehabilitation process shows how intrinsic storytelling is to Sheneland. In their world, the storyteller is a powerful figure, and when he speaks the entire court goes silent. This is keeping in mind that he is not telling myth, but history, and fairies know that they could receive such a punishment for immoral behavior. As the teller, Story is charged with not just safeguarding Sheneland’s history, but the values of the society.

Later in the book, Story again acts as moral compass. Aunt Spite sneaks into Elfin Court wearing a mask. The tale he tells her is even darker than his previous one. “The Enclosed Garden on the Border of Sheneland” opens with the image of a solitary woman wasting away in a garden of sickly fruit, surrounded on all sides by high walls, repeating “It is all my own. It is all my own.” The storyteller then relates how she came to have her garden, stealing the inheritance from her sisters and building walls to keep people off her land. Parr’s language in this passage evokes a feeling of dread and despair. The image of the emaciated woman slowly wasting in her garden is the stuff of childhood nightmare.

On one hand, Parr is using the language of Tragedy to warn children against greed and avarice. On the other hand, the character of Story is doing the same with Aunt Spite, fulfilling his role in elfin society. His presence, like that of a priest, is chiefly benevolent. It is implied he knows Spite’s true identity, but he is trying to warn her for her own good. Story has an important part in the novel’s climax, securing the final victory over Aunt Spite. Without revealing too much, it can be said that Story’s intervention has to do with the revelation of truth. Thus, it is not only the desire of the storyteller, but his duty, to bring the story to a resolution. Per his status in fairy society, it is only proper that he be the one to reveal the final truth.

Tuflongbo’s adventures among the Aplepivi has a wonderful child-like logic to it. In his story, the End of the World is a giant brick wall. He climbs over this, to the place where fairies cut up old moons to make stars, and a rambling series of events follows. Parr has fun playing with the fantastical nature of her setting: these thoroughly impossible events are portrayed as great sociological insights for the academics of Sheneland. Tuflongbo’s adventures are as innocent and fun as the other legends are dreary. It is interesting to note how revered Tuflongbo is at Elfin Court, with a rank equal to Story’s. He has been appointed by the Queen herself to travel to distant lands. In this realm, whimsy is important enough to receive government mandate.

Parr offers a great deal of variety in her legends and, as a reader, I had to marvel at the diversity of her fairy stories. “The Ugliest Cat” is a Brothers Grimm tale; “The Enclosed Garden” is a Tragedy; Tuflongbo’s tale is adventure. “From Sheneland to Shadowland” is something else entirely.

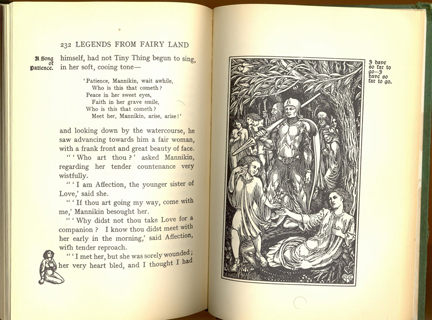

It occurs after the main plot of Fairyland goes into effect. Prince Glee and Tuflongbo go on a Quest to rescue Princess Trill. Naturally, they face many obstacles, and have certain magical talismans to help them along their way. Glee and Tuflongbo are trapped by Giants and put into a well, to be baked into a pie later on. Through a crack in the wall, they have a vision of Mannikin Hope. Another prisoner tells of Hope’s journey from Sheneland to Shadowland.

It is at this point where Parr ramps up the metaphysical nature of her world. There is an element of Hans Christian Andersen in the way she delves into universal themes. Mannikin Hope starts out as a little boy in the Chief City of Sheneland, who is taken in by a kindly Cobbler during a harsh winter. Before the Cobbler goes to sleep, for his work is done, he gives Mannikin shoes for his journey. From there, Mannikin takes the road from Sheneland to Shadowland, where his family now dwells. His journey begins in the morning and ends at night. He sees all manner of people on the road, meeting companions along the way. Mannikin does not always make the right choice in companions; for instance, he leaves Love on the roadside but travels with the unreliable Self-Help. In order to complete the journey, he must leave behind all his worldly possessions. Once in Shadowland, Mannikin is sent back into the world as Hope, lighting the dark places.

To an adult reader, the implications of the tale are obvious. Where Parr excels is the way she wraps her story in metaphor, using a succession of symbols to present life’s journey in a way children would understand. The lessons she offers are not easy, either. Mannikin’s journey gives much food for thought about the nature of Sheneland. For instance, he and the Cobbler are apparently not fairies. This does not matter; Sheneland is place where the metaphorical is made literal. Mannikin and all the people he encounters are abstracts, so they do not have to literally be elfin. Why does Mannikin have to journey to Shadowland when the Cobbler can just die? Because this is a world where logic is dictated by the story, not the other way around. Through this legend, Parr establishes Sheneland as not just a home for a specific mythological creature, but as a true liminal space: a living, breathing nexus of stories, ideas and life lessons, with no true borders between them. Mannikin Hope begins his journey as a person, and is reborn as a symbol. This is the magic of Sheneland. Mannikin’s story ties back to the main one when he gives hope to Prince Glee in his darkest hour.

Of course, all ends well for the heroes. Goodness is rewarded, villains are punished and love conquers all. What is left is the feeling that many fantasy novels strive for, but few achieve. I feel like I have been to Sheneland. I have followed these people, experiencing their world.

I do not know why Fairyland fell into obscurity, or why there is so little discourse on Parr as a writer. As far as conceiving secondary worlds, she was ahead of her time. George McDonald and J.M. Barrie had yet to conceive their own fairylands. Andrew Lang had yet to compile his “coloured” books which renewed interest in fairies. So why the lack of acclaim? Why is Fairyland no longer read to children? Why wasn’t it adapted into a BBC cartoon? Why hasn’t it received a gorgeous annotated edition? The fault may lie in that, like many of Dickens’ collaborators, Parr simply disappeared into his shadow. Hopefully, time will find a renewed interest in her body of work.

In case you can’t tell, I am not remotely impartial about this book. It is a treasure. A gem that I will carry with me, always, on my own journey from Sheneland to Shadowland.

Elwin Cotman is the author of The Jack Daniels Sessions EP, a collection of fantasy stories published by Six Gallery Press. He is a graduate of the University of Pittsburgh with a degree in English Writing, and is currently pursuing an MFA in Writing at Mills College. In addition to his collection, he has been published in The Front Weekly, The Fairfield Review, Outsider Ink, The Dirty Napkin, and Cyberpunk Apocalypse. He is currently writing a novella for self-publication next year.