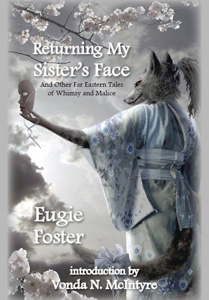

Returning My Sister’s Face

By Eugie Foster, 2009

Reviewed by Erzebet YellowBoy

Returning My Sister’s Face and Other Far Eastern Tales of Whimsy and Malice is a collection of twelve tales by Eugie Foster, a first generation Chinese-American who offers us stories drawn from Chinese and Japanese folklore. Foster’s work has been nominated for the British Fantasy, Bram Stoker, Southeastern Science Fiction, Parsec, and Pushcart Awards, and it’s easy to see why as she delights and delivers on the title’s promise. Here we have whimsy in the shape of a tea-kettle, and malice in a beautiful woman’s face. All of the familiar characters are in attendance: the wicked step-mother, the magical item, the trickster, the shape-shifter, and the young woman who defies the odds and sometimes the immortals themselves. As if those weren’t enough, Foster also provides us with a postscript to each story, speaking of her inspiration, history and influence. This makes for a more personal read, and it works.

Returning My Sister’s Face and Other Far Eastern Tales of Whimsy and Malice is a collection of twelve tales by Eugie Foster, a first generation Chinese-American who offers us stories drawn from Chinese and Japanese folklore. Foster’s work has been nominated for the British Fantasy, Bram Stoker, Southeastern Science Fiction, Parsec, and Pushcart Awards, and it’s easy to see why as she delights and delivers on the title’s promise. Here we have whimsy in the shape of a tea-kettle, and malice in a beautiful woman’s face. All of the familiar characters are in attendance: the wicked step-mother, the magical item, the trickster, the shape-shifter, and the young woman who defies the odds and sometimes the immortals themselves. As if those weren’t enough, Foster also provides us with a postscript to each story, speaking of her inspiration, history and influence. This makes for a more personal read, and it works.

Lovers of fairy and folk tales who crave, as I do, stories from cultures not their own will delight in these deceptively simple tales. They are layered with tragedy and superstition, with spirituality and most importantly, with a fine sense of the marvelous. Only “The Tears of My Mother, the Shell of My Father” is original to this collection; the others are reprints from Realms of Fantasy, GrendelSong, Cricket and others, spanning the years 2005 – 2008. I won’t comment on each of the tales individually, because I want you to savor this trove of treasures for yourself. I will tell you that “The Tiger Fortune Princess” is Foster’s take on both “Sleeping Beauty” and “Snow White”, and readers familiar with either tale will enjoy the twist. In “The Snow Woman’s Daughter”, we learn again not to question the devotion of one’s otherworldly lover, and in “A Thread of Silk”, we learn what it is to love. It seems as though we are right there as the lightning strikes in “Returning My Sister’s Face”, what I found to be the most profound of the stories. None of them let me down.

Many of the stories concern orphans who learn that their parents aren’t entirely human, and the theme of transformation runs thickly throughout the collection. The most common thread in these tales is the unquestioned existence of gods, demons and ancestral spirits. They are as much a part of daily life as is the kimono or a tea cup. They appear and disappear through the stories like wisps of smoke and thundering skies, causing chaos and bringing retribution to the unwary. Not all of the stories end happily, but that is as it should be. They do all end satisfactorily, and each provides us with a too-brief glimpse into the traditions and culture of the Far East.