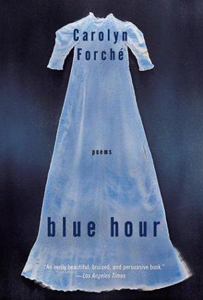

Blue Hour

By Carolyn Forché

HarperCollins, 2003

Reviewed by Tanya B. Avakian

Writing is a means of retrieving from consciousness a knowledge irretrievable by other means.

— Carolyn Forché, interviewed in 2008 by Sandeep Parmar

Carolyn Forché once saved my life. I would not meet her until almost ten years later, and it would be five years before she published Blue Hour, her greatest book and the one most completely in her own voice. It was Christmas Day and I spent it entirely alone in a basement apartment, reading and rereading The Angel of History and The Country Between Us while listening again and again to sacred harp singing on a cassette by the Word of Mouth Chorus, Rivers of Delight. The circumstances are private, but the experience is universal: at a particularly stressful time, to have been maintained in connection by the repetition of certain words and melodies. Many of the people who grew up with the hymns on the recording would have understood:

Carolyn Forché once saved my life. I would not meet her until almost ten years later, and it would be five years before she published Blue Hour, her greatest book and the one most completely in her own voice. It was Christmas Day and I spent it entirely alone in a basement apartment, reading and rereading The Angel of History and The Country Between Us while listening again and again to sacred harp singing on a cassette by the Word of Mouth Chorus, Rivers of Delight. The circumstances are private, but the experience is universal: at a particularly stressful time, to have been maintained in connection by the repetition of certain words and melodies. Many of the people who grew up with the hymns on the recording would have understood:

Farewell my friends I’m bound for Canaan

I’m travelling through the wilderness

Your company has been delightful

You who doth leave my mind distressedI go away behind to leave you

Perhaps never to meet again

But if we never have the pleasure

I hope we’ll meet on Canaan’s land.

Shape-note singing provides a close parallel to Forché’s art. The words are received from an older tradition than that practiced by many who can still appreciate it; the voices are often beautiful, but not quite pretty, some louder and wilder than others, at times sounding like different people telling very different stories. Even in the artificially polished version we find on the CD (a far cry from the babel of some of Alan Lomax’s original recordings), there is something not fully disciplined, more conversational than musical, with the occasional voice that asserts itself over the rest, hears itself singing, or doesn’t hear its lack of melody. The strength and grace of the music is in the number of voices and in a format that builds in imperfection, never allowing the loveliness to become flaccid or the untidiness merely sloppy. It may have its ups and downs, but it will not go through the motions.

Forché may even have saved my life before. At an age when some career choice was becoming urgent, I found my greatest talent to be for literature, my greatest interest to be in European literature about the Second World War, and myself to be in the perhaps common position of being just as horrified by some of Israel’s actions as by the anti-Semitism on some of the left. Her anthology of war poetry, Against Forgetting, appeared slightly too late to help me through the worst of this, but well in time to offer some consolation for not having turned completely New-World-materialist in the name of progressivism. Inevitably, Against Forgetting is not perfect; yet the beauty of it that it isn’t meant to be perfect. One can imagine it the way one would have done it oneself, many times, making it more of a participatory exercise to read than a visit to a monument; and one must be in awe of Forché’s courage when among many of her radical colleagues of the time, it was simply not done to admit that one read Abba Kovner and Edmond Jabès, though some may initially be jarred to find them among poets of the Middle Eastern conflict rather than the Holocaust. Today it is still the case among some on the left that one doesn’t read poets like Kovner and Jabès; but the abstention bespeaks a more sharply defined attitude (that best exemplified by Norman Finkelstein) than it once did. One of the most interesting revolutions of attitude among a broad spectrum of progressives has been in the normalization both of high culture and of eclecticism. If once upon a time it was not done to admit to reading Jabès because it was also not done to admit to listening to Bach, or pursuing higher education for reasons other than being radicalized, among those who would have taken Forché’s poems from El Salvador most seriously, today there is a lot more leeway; and if there is even a little understanding of European history as worthy of respect among New World extremophiles, we can thank her. I did not have a choice. My parents, second cousins, were born in Tallinn and Germany in 1932 and 1938, and came to the States in the fifties. My father fled the Russians as a child, to Poland where he remembered seeing many Jews on the street one day and none the next, and from there to Germany with the Russians again in pursuit. So if my own crisis of conscience in 1989 could not be eased by Against Forgetting, a lot could already be done by a description of a course Forché was teaching somewhere at the time. It’s no exaggeration to say that my thoughts ran to “She reads’¦ Akhmatova. She reads’¦ Nelly Sachs! There is hope!” Then, if memory does not deceive, I held the college catalogue to my breast and wept.

For those of us who love her, Forché has the distinction of making us feel that way about poetry even when we are well past that age. Today I often wish I could care enough about anything written for it to bring about that kind of reaction, while being relieved that it won’t. And I have outgrown the need to have my origins validated. I remain intensely grateful to Forché but I no longer need her to carry the torch. I understand that the most common reason why she at times inspires reactions close to loathing is that given by Norman Finkelstein, on Claude Lanzmann’s references to the difficulty of creating art about the Nazi genocides: “[It’s] twaddle’¦ drivel,” obviously meant to make us stop thinking about contemporary politics.

Forché would be the first to tell us that her fame has put her into a terrible double bind in this sense. The opposite pole of possibility open to her would be to go on writing explicit “protest” poetry in the sense that most people read The Country Between Us as representing. She did not write this handful of poems in order to take on a radical identity. Likewise, she has not written more enigmatically since then in order to confuse issues of justice and injustice. In such cases there is indeed a moral bias toward clarity, but as Forché put it in her introduction to Against Forgetting, the definition of a minimally functional society is that it contains space for experiences and relationships that are neither entirely private nor defined in a strict materialist sense by politics. She has called this the “social” sphere, somewhat in keeping with the insights of feminists who find that the experiences of women and children fall through the cracks when defined in too Manichean a way as either political or private. If anything, the missing element in Forché’s work has been that of the private. From earliest days she has been aware of herself as a link in history, beginning with her ties to her grandmother and others in her Slovak family.

In Blue Hour, Forché’s fourth collection, her subjects are private. They are not superficially autobiographical, unlike the early lyrics in her first collection, Gathering the Tribes. Her son appears as an allegorical figure, any woman’s child becoming any man. Forché herself has become faceless as a subject. Her perceptions here break down to such fine details that one is reminded of Erving Goffman’s famous observation in The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life: “The self, then, as a performed character, is not an organic thing that has a specific location, whose fundamental fate is to be born, to mature, and to die; it is a dramatic effect arising diffusely from a scene that is presented.” This insight is not unique to Forché; it is virtually a stock-in-trade of contemplative mystics, and the long poem “On Earth” attempts to rediscover the mental mode of prayer. But Forché differs from many postmodernists in that she does not embrace the fragmentation of consciousness in today’s world, though it may well lead us to the same conclusion. She sees it as endangering the forms of consciousness that allow us to engage in contemplation, and suggests that the only contemplation left to us is that of brokenness, though she also allows for the possibility that this in itself may be healing.

Her own relationship to this fragmentation is complicated. Perhaps suffering from post-traumatic stress after her visit to El Salvador, Forché experienced writers’ block for many years. She has talked of feeling broken, unable to complete a poem, and in fact she has published relatively little of her own since — The Angel of History and Blue Hour are each thin books. Yet she has become very famous for her brokenness. This statement leads to other thoughts which I would hope are taken entirely in context and not as personal or professional criticisms of the poet. She cannot help the time in which she writes any more than we all can. It’s a time in which one cannot publish without being typecast, and in which the poet is damned if she does (reach people) as if she doesn’t (and remains in isolation, writing for a tiny audience). Forché comes as close as any American poet can to doing both. She makes no concessions to public expectations, writing in a more and more experimental style and giving only a few interviews and readings at a time. But she is one of the most recognizable poets in English, one of the few who is admired for the content of her character as much as for her gifts, and the popularity of her work would suggest that its confounding sorrow speaks for many. She is in this sense a brand name. Inevitably this has been her blessing and her curse.

Forché is always clear that she is one of us, a housewife when she is not teaching or writing, as beset by lack of time and the banality of errands as we are. And inevitably, she is a Western white woman. Regarding her increasingly mystical writings, Forché has pointed out that it is just that status which has moved her further and further away from the directness of her youth. She went on the radical lecture circuit for several years after The Country Between Us, which made her name with its chapter of moving poems about the war in El Salvador. Typecast as a political poet in the Marxist sense, Forché found a climate in which she had the same forty minutes, time and again, to get on the stage and be radical increasingly oppressive and untrue to the complexity of her own views. As she had made clear in The Country Between Us, she’d had the luxury of witnessing atrocities by her own idealistic choice and then, the luxury of fleeing home in time to save her life. Archbishop Óscar Romero, who was instrumental in getting her out, was one of the few Salvadorans to share that freedom with her, and had chosen instead to stay home and die. Moreover, Forché was expected now to be fluent in a way that was anti-metaphysical, anti-ambiguous, anti-reflective in any sense except that which would produce condemnations of American foreign policy, and while the disconnect between the world she had left and the one that she now realized she had “never left” provoked her half to madness, she was profoundly disturbed by the sense that contemplation was for the bourgeoisie. Expected to show up before auditoriums of sensitive young faces and traumatize them on cue, she could not help but see a disconnect between the personal quality of her own experience and what she was now supposed to do to others. It appeared to her that a humane society must have more room for privacy and authenticity of experience.

As mentioned: there were then, as there are now, people for whom being influenced by Terrence des Pres’ The Survivor: An Anatomy of Life in the Death Camps, let alone by Celan and Sachs, was a sign of having joined the enemy’s side. In those years of the first intifada, suspicion of anything European and specifically of any debt to the literature of the Holocaust was very high among progressives. Perhaps less understandably, it was also not quite done to take an interest in Eastern Europe as a locus classicus of horror, when some of the same progressives clung to a belief in Stalinism. The pendulum would swing in the opposite extreme during the mid-to-late 1990s, likely because the end of the Cold War left America with the need for a new narrative of moral superiority and our deus ex machina entry into World War II fit the bill. The need for a Western-friendly narrative of recent Middle Eastern history was much older, and the excuse of the Holocaust proved extremely tenuous after 9/11; but for a few years, the sudden accessibility of Europe, the disappearance of Cold War barriers and the realization that fifty years had passed in which America too was beholden to this history, allowed progressives to balance suspicion of at least the American-style Holocaust narrative with the sense that Americans might be sincerely interested in Adorno’s, Celan’s, and Primo Levi’s dark continent. Whatever the reason, there was a grace period for Forché’s interest in her own roots and in the experimental literature that had grown largely out of those very “bloodlands” during the middle of the waning century. Nor was her discovery of links between Eastern and Central European and other war-torn poetry, and writing styles more associated with the Lower East Side, entirely far-fetched. For instance, the Fluxus movement was started by Lithuanian refugees Jonas Mekas and Jurgis “George” Maciunas, and taken up by Japanese artists such as Yoko Ono, herself a war poet (her childhood resembling the film Grave of the Fireflies, and Grapefruit weirdly reminiscent of the poetic enactment of traumas on the part of everyone from Wiesel to Forché). Andy Warhol’s family shared a similar background to Forché’s grandmother, Anna Bassarova.

Today there is perhaps a glut of second- and third-generation interest in the terrain covered by Theodor Adorno and George Steiner; much of it is undistinguished, being located more often in supposedly embodied cultural memories than in long-term, firsthand experience of the survivors, their own or their children’s of them. Forché is not in this category, but her recurrent need to survive success points up the role of magic in this peculiarly demanding realm of art, and the difficulty encountered anywhere that magic plays a role — that what is touching in the fan can be bothersome in the star: here, specifically, the belief that creativity is magic. In the best sense, Forché has access to a more naïve way of taking the spiritual direction in poetry than is open to many: her own experience puts her in touch with ways in which words are things, causing pain as a knife does when their meaning is that of an instrument. If this is anything but an effete, self-consciously sensitive way of approaching poetry, it is also one with an inevitable metaphysical component. Forché strikes me as a real-life pilgrim. All the other ways of taking her — radical sibyl, Detroit Yankee in King Adolf’s court, and so on — are subordinate to her identity as a faith-based writer in the truest and least objectionable sense. She has earned this much, surely; once again, it bespeaks the sickness of our time that this too should inspire suspicion. People still tend to respond to Forché with equivalents of “What’s a nice girl like you doing in places like this,” and her real-life niceness — a sincerity and straightforwardness, a lack of what the British call “side,” and a stubborn benevolence of outlook — still tends to etherealize the understanding of a woman who grew up in very gritty surroundings outside Detroit, knew real, unchosen poverty at various times, and whose being a fan dignifies the Frankfurt School and Lévinas rather than their corrupting her.

Yet the dark places of Blue Hour, while they include Chernobyl and Beirut, are also places we all are going to visit and where we are finally going to go. “On Earth” bids farewell to the twentieth century in the voice of a baby boomer herself facing mortality. It has been greeted as Forché’s most avant-garde poem, but it should not be read as if to understand it one must be a trauma buff, or an enthusiast of experimental poetry. One need only have lived long enough to know people break and are mortal. Blue Hour‘s title comes from a French expression for the time between night and dawn. It is concerned with boundaries and membranes, points at which one thing becomes another. The images of historical extremity flicker in and out among the throng of personal ghosts; one can imagine them all convening as in Hades, among the shadows of a pine forest, a blue field of snow, viewed through a window at three or four in the morning. Blue Hour has been compared to Ginsberg and Whitman; my recurrent thought is of Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries, where an old man revisits the scenes and characters of his youth with a tranquility for which the price is his awareness that he is now alone with them. But Blue Hour has another dimension, close to speculative poetry. Chernobyl comes up more than once, and the prevailing political sensibility resembles that of William S. Burroughs: a wide-eyed, nearly catatonic paranoia intercepted mainly by the act of cutting and redistributing an unbearable consciousness into new patterns, one of which may offer the key to endurance if not escape.

The Angel of History was one long poem that read at times like a collection, even an anthology, the ghost that rose from the assembled wreckage of Against Forgetting. Blue Hour is a collection that reads like one poem. While nine poems precede the 46-page poem “On Earth,” and while they are intelligible on their own, they do not stand alone; they blend easily into this one work, representing the extreme of Forché’s humility and of her chutzpah. Its format is abecedarian, the lines organized by letters of the alphabet, and its language is deliberately naïve. As in the famous anonymous poem that begins “I saw a peacock with a fiery tail,” all is in the composition rather than the sense. Its first lines appear to be telling us how the poem is meant to strike us: “–with the resistance of a corpse to the hands of the living–“. Pathos breaks down fast over the full length of “On Earth,” and it resists being read easily with any meaning at all. Even as it begs a portentous and by now familiar interpretation in its opening lines, especially “open the book of what happened” — on its own, a beautiful and moving phrase for the work of trauma — it undoes facile readings of any kind; even more than any of her previous work, its subject is how little simple, and yet how disturbingly little complicated in an intellectual sense, “what happened” turns out to be. It need not be read as a gloss on the last century at all, or a warning to the next, though it is all that; it will serve as a guide through the memory, and experiencing fully only in memory and imperfect relationships, of any great trauma. One tracks the poem like the movement of waves, isolating lines in which they break against land and others in which they recede in foam, and experiences it best in retrospect; the reader may decide for herself the moment at which the longed-for, hopeless consolation possibly occurred.

I’ve already compared the plot of Blue Hour to Bergman’s Wild Strawberries. Visually, “On Earth” also resembles a film by Andrei Tarkovsky, with similar demands on one’s attention span and a similar effect of the senses being at once ravished and deprived. There is a cornucopia of images, a great heterogeneity, but little real variety; there are many, many nouns, with no context for the object other than that created by the passage of unseen events. The poem is likewise drenched in spirituality without apparent purpose, or even metaphysics other than the faith that there is another side at the end of experience. To enter into the experience with any irony at all, any preconceptions about the value of one’s own objective consciousness, is possibly to miss it. And yet as in Tarkovsky’s films, nothing happens that is in any way impossible to understand objectively. There is no mystification, only a transparency that mystifies. Everything is literal. Nothing is to be analyzed at first, and everything is to be enacted by means of attention; one does not read so much as watch and listen. Other than what we know through Forché’s prior work and reputation, while “On Earth” is haunted by disaster, we do not witness it; the disaster can be assumed to have happened, or to be happening, also on that other side of experience or consciousness.

While we learn almost nothing about it, the telling of this disaster might still leave those whose griefs are private and deliberately contained with a sense of being violated. Forché’s language is never sentimental or poetical in itself, though it invokes shamelessly poetical, rather Gallic tropes on select occasions, like the white doves that “batter the wind” here and there throughout The Angel of History. The very stiffness and seeming apartness of these touches strips them of sentimentality, as the freed doves complete the trauma survivor’s manifesto in Georges Franju’s Les Yeux Sans Visage (whose heroine, Édith Scob, resembles Forché facially); though it is understandable why not all critics have responded to them as such. Finding the key to “On Earth” is going to be a personal endeavor for everyone; one possibility is to pull apart those lines that seem literary in this way and read them together, followed by others in which no artificiality is possible. One has no difficulty guessing at a measure of pastiche in these lines, for instance — here some more Franju, perhaps in Judex, there some Latin American soap opera:

a corpse broken into many countries’¦

a life in which nothing is lived’¦

a memory through which one hasn’t lived’¦

a war-eyed woman’¦

a white rain, then your face becoming another’s’¦a hotel haunted by a wedding dress’¦

a locket’s parted lovers face to face’¦

a veiled window where appears a revenant’¦

a woman rubbing the mirror until she is gone’¦

air filled with ash, notebooks with sorrowing ink’¦

And then one encounters others, whose only chance at melodrama is if they came singly, but they don’t:

biting hard the fear

black corn in the fields, crib smoke, and bones enough to fill a sack

black fingernails, blue hands, lost hair

black storms of dream

black with burnt-up meaning’¦

bones smoothed by water

book of smoke, black soup’¦corn black in the fields, crib smoke, bones, a rib cage’¦

canticle, casement, casque, cerement, cinder’¦

flowering trees: trumpet, bottlebrush, cassia, frangipaini, flame, sea grape

flowers rotting on mounds: air plant, allamanda, amaryllis, spider lily, bougainvillea, shellflower,

hibiscus, ashanti blood, trumpet vines, oleandergarbage fires along the picket lines

gasoline coupons and rations, an event no longer remote

Georg leaning against the winter pine eating a sparrow

ghost hands appearing in the windows, rubbing them clear

ghost swift, grisaille, guardian spirit

For some, the thought that any one consciousness has this power — of unmaking as much as making — must be a fairy tale, all the more so if it is a consciousness in the West. Forché’s self-forgetting as a poet is in its way as willful as Simone Weil’s as an activist. So many years after Gathering the Tribes, her identity now is cosmopolitan and only partly tribal. But Forché’s tribal Slavic identity is still apparent in the revulsion “On Earth” shows for the destruction of kin privacy in an age of atrocity: the sense that now, one grieves like this about things that are none of one’s business. And as the poem goes on, that seems to me to become its ultimate note of tragedy. Its story is one of a farewell to empathy, all the ways in which people do not come together in pain. Empathy falters or isn’t good enough; it intrudes or leaves a person alone; the bearer of empathy is not personally good enough to be welcome here; there are too many to feed; the circumstances make it impossible, in the sense of being frustrating or of being literally impossible. The words are there but may not be spoken. The words are not there, but babble comes out. Selfishness, confusion and wickedness get in the way, one’s own and others’. It would be comforting to add “and yet it must all be done,” but “On Earth,” for once in Forché’s work, does not write out of an imperative so much as an inevitability — the doing of empathy continues like tape chatter long after any hope of its relevance has gone. Empathy persists because human selfishness and folly are inexhaustible: we give up the belief that it matters, last of all. “How” and “I,” two important words in the English language, have only frustration associated with them, over less than half a page:

how did this happen? how it always happens.

how it reads its pasthow secretly you died for years, on behalf of all who wished for themselves a private death

how the soul becomes an inhabitant of fleshI am alone, so there are four of us

I am here, blowing into my hands, you are in the other coffin

I can’t possibly get away, she saidI lit a taper in the Cathédrale St-Just, a two-franc candle, birds flying in the dome

I remember standing next to his bed

I see myself in their brass coat-buttons but not in their eyes

I stand on the commode for a glimpse of it

I tried once, it was just before the war, and she had no time for me. I can’t possibly get away

I was to bring him music for the left hand

Grace is not in relationships, but in the nouns that march on as if in oblivion:

light and the reverse of light

light impaled on the peaks

light issuing from the wind’s open wounds

light mottling the forest floor, crows leaving one limb for another

light of cinder blocks, meal trays

light of inexhaustible lightlighted paper sacks sent downriver to console

like the handkerchief road

like the whispering in a convent garden

like tomb flowers, the ossuary’s skull works

lilac and globeflower, clouds islanding the tilled fields

The ultimate message of this poem appears to be that as death approaches (or as great pain is endured), the social in Forché’s sense must be given up. Others must be allowed their aloneness and one’s own must be accepted. The healing of which Against Forgetting was meant to speak must be allowed to fail for the individual in private. At times it is possible to read the meaning of this as salvific, a form of emptying-out of the self that allows the social membrane not to exhaust itself, but to continue consoling others up to the point at which they, too, must give up:

memory did not survive that loss of sequence

memory does not interfere’¦near the lake, where the fireweed was

neither a soul nor a body

neither for us nor near itself

never repeating itself

nevertheless, noumenon, novembernew pasts, whole aeons are invented’¦

no breath of God, no words, and no possibility of restoration

no content may be secured from them

no one prayer resembling another’¦nothing as it was

nothing other than mind

nothing was exiled from itself

now and again like a voice grown suddenly tired’¦their bedclothes soaked in music

their bruises, aubergine

their refusal to accompany us furtherthere is a reason you have lost him. for the rest of your life you could search for it

there is no absence that cannot be replaced

there is no reason for the world

there was black corn in the fields, crib smoke, and bones enough to fill the sack

there was no when there

there was nothing that wasn’t for sale’¦what crawled out of the autumn wood was dementia

what did we retrieve? empty spectacles?

what do these questions ask?what do we have to forget?

what end? what uniformity?

what fragmentary light?x does not equal

you spit out your teeth, give it up’¦

your things have been taken

your things have been taken awayzero

One still hears some of the voices against Forché, those who would point out that only an American would be able to expose herself to a civil war voluntarily and then be able to afford to spend thirty years in partial recovery. Yet perhaps it privileges in its own way to spend time exclusively with such concerns; perhaps it presents the right-thinking Westerner as too good for any private life — just as if nobody in Palestine or Thailand or Cameroon has had any private interests or experiences, any delight in literature or spirituality for their own sake, or indeed any private horrors; as if no rapes or automobile accidents or final illnesses or misunderstandings between friends ever brought them to such a dignified exhaustion, such a need to accept what does not end. Indeed it is worth keeping in mind that the European poets who influenced Forché were humbled just as we may all deserve to be again, by our own selfishness and folly and not-enoughness for a world that has outgrown us now as in 1939, and part of what they were asking for on a plate was the awareness that people in any culture are flesh.

It would be easy for Carolyn Forché to write poetry that one could love without respecting it; what she has achieved instead is a poetry that some who don’t love it, such as her tireless nemesis Eliot Weinberger, have ended by respecting. If the whole were not greater than the sum of its parts, if what went into the parts were not flawed, and if the outcome did not at times seem unfinished, Carolyn Forché’s work would not do what it means to do; nor would she so stubbornly resist any attempt to imitate her, although to do so seems easy, as easy as shape notes.

I know dark clouds are hovering o’er me

I know my way is rough and steep

But beauteous fields lie just before me

Where the redeemed their vigil keepAnd when my journey’s finally over

When rest and peace upon me lie

High o’er the roads where once we travelled

Silently there my mind will fly.