by Marta Pelrine-Bacon

Lily had to remember not to let her daughter see the apples. Whenever Miranda saw an apple, she began to scream. Even a picture of an apple brought tears. It made the grocery store near impossible. Alphabet books were difficult. So many off them started off with A is for apple.

Lily had to remember not to let her daughter see the apples. Whenever Miranda saw an apple, she began to scream. Even a picture of an apple brought tears. It made the grocery store near impossible. Alphabet books were difficult. So many off them started off with A is for apple.

Once Lily carefully cut an apple into cubes. She pushed the skin and core deep into the trash. The few cool whitish cubes she set on a blue plate next to cubes of cheese. Miranda had skipped into the kitchen and screamed.

It took weeks for Miranda to stop accusing her mother of trying to poison her. All white food became suspect. Apples on television made Miranda cringe, and eventually the girl stopped watching television all together.

Every year, on the first day of school, Lily tried to explain this to the teacher. The teachers nodded, their eyes on all the kids, trying to sort out the troublemakers and the pets. They didn’t understand. They didn’t understand until Miranda began screaming. The girl afraid of apples. By third grade all the teachers, kids, and parents knew.

Sometimes another child snuck an apple into the girl’s bag, and they would all laugh when the apple rolled out to her feet. She screamed and jumped on a desk or fell over a chair. The teachers rolled their eyes. “It’s only an apple.”

“What happened?” other parents asked. Her in-laws asked. Her husband asked.

Lily didn’t know. Of course, she suspected her mother. Miranda’s grandmother whispered fantastic tales as she shuffled about the house. The old woman didn’t sit down and tell stories properly. She muttered them under her breath. She leaned into the washing machine grumbling about dwarves. While going out to check the mail she said things about hunters and hearts in boxes. At the grocery store she mumbled about poison. The store manager asked her to leave. She frightened the customers.

Sometimes Miranda’s grandmother sat in the kitchen, clutched at her throat, and coughed as if she were choking. Lily used to call an ambulance, but so many calls and so many accusations of poisoning ended with social services at her door. They talked of a nursing home, but Lily didn’t want to send her mother away.

Now in the fourth grade, Miranda had mastered controlling her screams. She saw an apple and bit the inside of her cheek until it bled.

Miranda loved to take her grandmother for walks. Her grandmother was slow. They had to stop often and sit. They watched people go by. Her grandmother made up stories about everyone they saw. On walks with Miranda her grandmother’s mind was clear.

Years went by, Miranda grew up. Her grandmother never seemed to get older. Her habits stayed the same. Her stoop, her mutterings, her coughing fits all stayed the same. She was her granddaughter’s best friend.

“Miranda,” Lily said one afternoon at the kitchen table. “You’re about to be eighteen soon.”

Miranda sipped her coffee.

“You should get out more with people your own age.”

Miranda added more sugar to her cup. “You always say that.”

“Well, it’s still true.”

“I’m fine.” She stirred her coffee hard. Coffee splashed on the table.

“You spend too much time with your grandmother.” Lily hadn’t touched her coffee.

“Who else is going to spend time with her?”

“You’ve never even had a date.”

“That would make most mom’s happy.” She gulped at her coffee now.

Lily leaned forward. “Miranda. Most mom’s want their children to be happy.”

“Don’t worry, Mom. My prince charming is out there. I’ll meet him when the time is right.” She drank the last of her coffee. “I promised grandmother an afternoon walk to the park.”

They got to the park late in the afternoon. All the colors were washed out by the afternoon gold of the light. They sat on a bench with a view of the fountain, the ice cream vendor, and the man selling balloons. A child ran up to them and handed them a flier for the circus. Only in town until the next full moon, the flier said.

Her grandmother read the flier again and again. “There are dwarves in the circus,” she said.

Miranda laughed. “Why would they agree to be in a circus? Aren’t they just like everyone else?”

Her grandmother patted her knee. “To see the world. To meet the right people.”

“Mom would never let me go. It doesn’t even begin until 10pm. Look.” She pointed to the paper.

“Your mother doesn’t understand you. Like my mother didn’t understand me.” The flier shook in her hand.

“You’ve never told me anything about your mother. What was she like?”

Her grandmother shrugged. “She never wanted me. That’s all I want to say about her.” She put the flier in Miranda’s hand. “I had great adventures a long time ago. It wasn’t happily ever after, but I was happy.”

Miranda put a hand on her grandmother’s shoulder. “Aren’t you happy now?”

“Look at my old hands. They look just like my mother’s.” She tapped at the flier with a bent finger. “This. This, Miry. This is your adventure. I want you to go.”

“Grandmother. I can’t just go.”

“I ran away when I was your age. You can do me so much better.”

They didn’t talk about it anymore that evening. The family went to bed as always. But in the morning, when Lily went to her daughter’s room, she found the bed empty. “Mother,” Lily said, sitting on the edge of her mother’s bed. “Have you seen Miranda this morning?”

Miranda’s grandmother curled her fingers at her throat. “Sweetheart,” she said. “My room smells too much like apples.”

Artist/author statement by Marta Pelrine-Bacon:

“I write modern fairy tales and make art from the pages. Â I’ve lived happily ever after in Austin for almost 15 years.Â

Â

Where I grew up–on a long stretch of road in central Florida–my father told me a witch lived in the abandoned house under a cluster of punk trees and moss. Our own house faced a lake big enough for an island in the middle where blackbirds settled for the sunset. Florida is’”in case you don’t know–a perfect place to develop an interest in sharp objects. That’s why I write stories with odd twists, turns, and edges.

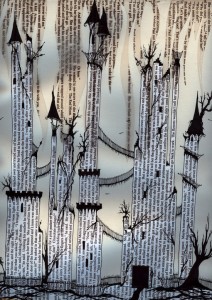

But I left home at 17 to study English and writing in Indiana. Ended with my Master’s Degree from Kent State University. To see something else of the world I joined the Peace Corps and taught English in Bulgaria for two years. But one way or another I always made art and wrote. I’ve always loved paper, ink, scissors, and glue and my art incorporates as much of these things as possible. The art is made of different types of paper–printer paper, archival paper, tracing paper, and transparencies. Also used are pens, pencils, and charcoal pencils, strings, and sticks. Â

Â

All the words in the image included here are from my novels and stories. The images are not representational of the writing, but are images I like and find compelling–and perhaps that capture the mood of the story.

Â

I do work with other people’s words, too. I created a CD cover and insert art for a musician using his lyrics and notes. I’ve also used favorite poems or words in other made to order pieces and pieces for fund raisers. My work has been shown three times over three years at Genuine Joe’s Coffee House in Austin and two years in Art City Austin. My work has appeared in Onomatopoeia Magazine.Â

Â

I make art and write stories in a cluttered corner of my living room late at night while my family sleeps. Art, I believe, can be made anywhere by anyone. Make something. Â Â

Â

Read more at mapelba.com or join my facebook group: Words Are Art.”