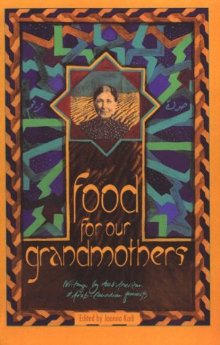

Food for Our Grandmothers: Writings by Arab-American and Arab-Canadian Feminists

Edited by Joanna Kadi, 1994

Reviewed by Tanya B. Avakian

This excellent collection of essays, memoirs, poems, and other writings by Middle Eastern (nearly but not all Arab) feminists in North America announces its relevance to sff writers as soon as one gets to the table of contents. Hoda M. Zaki has contributed an article called “Orientalism in Science Fiction,” taking aim at Dune, but also at Joanna Russ (1937-2011) for her stereotyped Islamic dystopia in The Two of Them. One should not be surprised, but it may still come as a shock. For antiracist and feminist readers of science fiction, Joanna Russ is one of the “good” writers, author of a seminal text in How to Suppress Women’s Writing that has also been used as a casebook for race. It is a useful example of the politics of reputation. There is no reason for Russ to be “good” and others to be “less good” just because Russ was once seen as a radical, and has written in caring terms about race. Much of the discourse around racial sensitivity in sff has been personality-centered, sorting out the “good” people from the “less good,” but Zaki’s insights suggest that it is essential to get away from personalities: it is entirely possible for an individual, limited by time (generation) and space (country of origin) to be good in some areas and less good in others. This is not to excuse Russ’ bigotry in The Two of Them; it is rather to challenge readers to find appropriate role models for “good” on this particular topic’”Arab feminists, for a start, who at least know what they are talking about. The issue that Zaki leaves us with implicitly is why there was no Arab voice in sff to balance that of Russ, the equivalent to her Ashkenazic lesbian perspective relativizing the “less good” and, for some, maybe allowing the “good” to shine more brightly. Once the answer might have been that Arabic lesbian feminists did not exist or were not writing science fiction and fantasy. Today that isn’t an answer.

This excellent collection of essays, memoirs, poems, and other writings by Middle Eastern (nearly but not all Arab) feminists in North America announces its relevance to sff writers as soon as one gets to the table of contents. Hoda M. Zaki has contributed an article called “Orientalism in Science Fiction,” taking aim at Dune, but also at Joanna Russ (1937-2011) for her stereotyped Islamic dystopia in The Two of Them. One should not be surprised, but it may still come as a shock. For antiracist and feminist readers of science fiction, Joanna Russ is one of the “good” writers, author of a seminal text in How to Suppress Women’s Writing that has also been used as a casebook for race. It is a useful example of the politics of reputation. There is no reason for Russ to be “good” and others to be “less good” just because Russ was once seen as a radical, and has written in caring terms about race. Much of the discourse around racial sensitivity in sff has been personality-centered, sorting out the “good” people from the “less good,” but Zaki’s insights suggest that it is essential to get away from personalities: it is entirely possible for an individual, limited by time (generation) and space (country of origin) to be good in some areas and less good in others. This is not to excuse Russ’ bigotry in The Two of Them; it is rather to challenge readers to find appropriate role models for “good” on this particular topic’”Arab feminists, for a start, who at least know what they are talking about. The issue that Zaki leaves us with implicitly is why there was no Arab voice in sff to balance that of Russ, the equivalent to her Ashkenazic lesbian perspective relativizing the “less good” and, for some, maybe allowing the “good” to shine more brightly. Once the answer might have been that Arabic lesbian feminists did not exist or were not writing science fiction and fantasy. Today that isn’t an answer.

Joanna Kadi’s collection aimed for some of the assumptions about “good” and “bad” in the women’s movement in very much the same way as Hoda M. Zaki’s article continues to aim at “good” and “bad” in sff. Kadi is best known for Thinking Class: Sketches from a Cultural Worker. Published in 1996, this was a keynote work in popularizing the concept of the interconnectedness of oppression, not necessarily in the sense of finding a “magic bullet” to stop all oppression (the kind of thinking most often satirized by the misnomer “political correctness”). In 1994 Kadi was brave enough to raise the question of whether there is such a thing. One of the most salient characteristics of Arab feminism is its resistance to being made yet another marker of excellence for white feminists and progressives to take on board. At the time of publication one way to do that was to engage in the politics of sympathy, not yet coping well with race but doing so more easily when it came to immigration. Though immigration is its central theme, Kadi’s collection pointed a way forward, past the often querulous emphasis on “brokenness” and “fragmentation” in postmodern theory and toward the beginnings of earned confrontation with the reasons for brokenness.

The collection is naturally dated in some ways, though its core concerns remain painfully contemporary. There are the obligatory nods to then-fashionable postmodern theory and the sense of “things falling apart” that prevailed at the turn of the century. Marilynn Rashid introduces herself by writing “I am a piece of the cultural entropy of the age, forever falling away from many centers.” She points out that she has “kept her name” but reflects that it is her father’s; her non-Arab mother’s was that of her own father. When it comes to “returning to one’s roots,” Rashid points out that it is impossible:

If we truly knew who we were, our names would not be such a problem. It is difficult to find one’s way in a world divided not only by war and racism, but by freeways, television, and the technological projects of so-called progress. If we could, in fact, go back where we came from, as some would like us to do, we would still not find ourselves, for those places are changed or destroyed or occupied or part of the same industrial grid we find ourselves in here. And some of us, many of us, would have to cut ourselves into twos and threes and ship pieces of ourselves all over the globe. And surely that wouldn’t help our sense of fragmentation.

By contrast Joanna Kadi’s own essay, “Five Steps to Creating Culture,” has some of the cavalier attitude to the concept of culture that tended to balance such pessimism’”if freeways and television were enough to destroy culture or undermine it as a source of nourishment, recipes were enough to resurrect a faith in culture that was gainsaid by the age’s concern with political or commercial taint. Kadi puns on culture by describing the steps to making a culture for laban or yoghurt, and associates them with political integrity:

Step I. Heat the milk and let it reach the boiling point. Reach the boiling point. I have reached the boiling point many times. I know about Lebanon’s suffering, Palestine’s dispossession, Iraq’s devastation. I know how many times I have been called names, how many Arabs have been beaten on American streets’¦ All of this knowledge is what leads me to the boiling point. It makes me angry. And I think it is good for a cultural worker to be angry, not with the kind of anger that poisons our insides and drives people away, but with the kind of anger that gives us momentum and courage’¦ Step II. Check to see if the milk has cooled enough. When you can keep your finger in the milk for ten seconds you will know it is the right time. The knowledge resides in the bone, in the body’¦ I wait to write, wait until the time is right, until anger is not the most overwhelming emotion. The time is right only when thoughtful reflection, love and humor catch up with anger so that they all mix together.

All these things are worth having, and it is no fun for me to say that I’ve seen too many written or filmed pieces ending with ethnic feminists happily cooking together for me to read this piece with pleasure. I can see people I know and love being moved by Kadi’s words as I type my own rejection, when her piece is not mine to refuse. Others who may identify with it are encouraged to benefit. But one only needs to read a few of the pieces Kadi has collected to know it is all more complicated than she presents it here. Beginning with a desirable outcome risks sentimentality; worse, it risks confusing integrity with an inevitable measure of sentimentality about either brokenness or essentialism (“in the bone, in the body”), implying that either means we “truly know who we are.”

For me the warning bells begin with sentimentality about anger. Kadi knew what she meant in beginning her “culture” with anger, but not all readers can be presumed to know. Although there is a great deal of reason for anger in these essays, Kadi’s writers usually do not write about anger with pride in the manner that many American progressives are used to. It is not a marker of integrity. (Kadi herself has written elsewhere about the difficulty she faces in accepting her own anger, after a lifetime of internalized racism and classism; the commentary here is restricted to this one essay.) In addition to the writers’ terrible sense of helplessness, this may be due in part to the fractured sense of identity referred to again and again. All people get angry, but it is a luxury to be able to respond with the decisiveness of an undivided self. If one’s identity is multiple, the concision of righteous anger is an expensive luxury in situations where it is often entirely appropriate, such as the political situations in Iraq, Palestine and Lebanon during the time of writing. I do not want to say that Kadi is wrong to valorize the right kind of anger, but instead to point out that it may be a misprision to present most of these writers as possessing the anger of the progressive cultural worker. What we can fairly assume in many cases is the anger of the victim, which shrinks to a pale shadow beside her grief. If there is any one emotion that Kadi’s writers associate with personal honor in the expression, it is an overwhelming and destabilizing sense of grief, to which rage is only the handmaiden. Naomi Shihab Nye gives voice to this desperation in a touchstone poem:

Blood

“A true Arab knows how to catch a fly in his hands,”

my father would say. And he’d prove it,

cupping the buzzer instantly

while the host with the swatter stared.In the spring our palms peeled like snakes.

True Arabs believed watermelon could heal fifty ways.

I changed these to fit the occasion.Years before, a girl knocked,

wanted to see the Arab.

I said we didn’t have one.

After that, my father told me who he was.

“Shihab”‘””shooting star”‘”

a good name, borrowed from the sky.

He said that’s what a true Arab would say.Today the headlines clot in my blood.

A little Palestinian dangles his toy truck on the front page’¦

I call my father, we talk around the news.

It is too much for him,

neither of his two languages can reach it.

I drive into the country to find sheep, cows,

to plead with the air:

Who calls anyone civilized?

Where can the crying heart graze?

What does a true Arab do now?

It’s as if the anger valorized by the American or American-influenced feminist can be presumed to exist in Nye, as an Arab, even before she is a feminist, and yet its meaning has been pulverized by history: all that is left to her is to turn it on herself. The creative anger of the “cultural worker” (a Marxist-inflected term for a person blending creativity with activism) reads as a pale substitute, even if that is only a matter of how it draws the reader’s attention to the same thing.

The search for integrity preoccupies a majority of writers in the collection. In 1994, most of them blamed themselves, global politics, or both for their sense of lacking it: racism and sexism in the Arab world are touched on but not usually named as deal-breakers, much as among the Franco-American women profiled in Kristin M. Langellier’s Storytelling in Daily Life. Seldom if ever do the writers report that they cannot identify with their background at all, or communicate with their families. This is very different to the experience reported in memoirs such as Charleen Touchette’s It Stops With Me or Arlene Voski Avakian’s Lion Woman’s Legacy, which also feature heroic grandmothers. (It may still be true for some of Kadi’s writers and just go unreported.) Also different is the seeming unwillingness of Kadi’s writers to identify with a progressive political community as their new home. Kadi herself expresses that wish by implication, but hints at its difficulty for her as well, given what divides her from Western activists. The essay that comes closest is Bookda Gheisar’s “Going Home.” Gheisar is clearly involved in a positive choice of cultures: “The trouble with looking for a home in the United States is that the mainstream patriarchal and racist culture will never allow me to make this my home. I am not allowed to be angry or criticize the American system because then someone will always say, ‘˜If you don’t like it here, why don’t you go back to where you came from”¦ It would be easy to give up, considering all the violence, wars, and injustice that surround us everyday, but I continue to find my power by connecting with other people of color, writing, and finding my voice. And I continue to follow my heart to a place where I can fully belong.”

Like Kadi’s in her essay, Gheisar’s ideals represent things well worth having. Both Kadi and Gheisar write from a standpoint perspective as defined by Nancy M. Hartsock and others. Hartsock distinguished the feminist standpoint from a “woman’s point of view” by locating the feminist standpoint in the conviction that relations between the sexes must change. Born to a privileged background in Persia, Gheisar, like most standpoint activists, finds her “home” in the people working with her for this change and others, to the extent that different concerns can find common friends. Feminist essentialism by contrast appears in Nada Elia’s article “A Woman’s Place is in the Struggle.” “In my mind, we women have measured our achievements in terms of masculinist history for too long. To examine international feminism in terms of the [first] Gulf War would, once again, validate the patriarchal, militaristic discourse feminism seeks to undermine.” But she rejects essentialism about her own national origins. Here the standpoint shifts. As much to the point, when it shifts from feminism to national or racial identity it finds no one place to land:

I am Lebanese, or so I tell people I think I will not be seeing again. Friends get the longer version. My parents are Palestinian. My birth occurred in Iraq. We moved to Beirut when I was still a baby. I grew up in Lebanon. I also make it a point to specify that although my family is Christian, I grew up in West Beirut, that is, that part of the city the media refers to as “mostly Muslim.” Why should my narrative be simple? Can any narrative be simple if one of its themes is related to the Palestine question? I also identify with Muslim culture, because it is my experience that, whether you are a believer or not, you carry values of the predominant religion. Thus, in the United States, you need not be Christian to identify with certain Christian values, or to punctuate your calendar with Christian dates. Similarly, I believe Islam to be part of Arab culture, my culture. I am sure the Lebanese Christians will choke on this one’¦

This anti-essentialism was once the certificate of excellence among academic progressives, and provided the ticket to choose one’s own culture within progressivism as Bookda Gheisar does; but its being valorized for a sense of brokenness ignored the moral essentialism, implicit in the privileging of the choice, in a way that Kadi’s writers largely do not. Gheisar welcomes it that she has a choice, as do nearly all of Kadi’s writers in one way or another. At the same time Gheisar and every single other woman represented here is aware that the existence of this choice on her terms as a person of multiple identity, rather than simply as a woman, represents an undermining of her host culture that is no fin-de-siècle accident. It means she is not her sitti and not by her own, her parents’, or her sitti‘s choice. Most commonly, the writers describe having to “pass” in all their cultures. We can see the postmodernism of the 1990s on its way to becoming the antiracism of the 2000s. The postmodern perspective was fairly described by Marilynn Rashid in terms of a sense of loss and being forever compromised, the loss often as not blamed on a multicultural, technological global village that was still embraced up to a point. The antiracist perspective takes a clearer moral stance against the need to give up so much by asking who demands that it be given up in the first place: who is to say that there is anything mutually exclusive about being Arab and American, for instance, or feminist and either, if it were not for enforced systems of oppression that mark one pole as a privileged state and the other as not.

The most significant marker of the collection’s publication in the nineties is that most of the writers either identify as white or describe themselves “passing” as white. Laila Halaby puts her finger on it in a poem called “Browner Shades of White”:

Under race/ethnic orgin

I check white.

I am not

a minority

on their checklists

and they erase me

with the red end

of a number

two pencil.

This has changed at least among Middle Easterners who identify as antiracists, enough so that it is a telling surprise to find how many women not only passed as white twenty years ago, but were preoccupied by their ambivalent relationship to whiteness. The ambivalence is not easily resolved. Some Middle Eastern groups such as Armenians are officially white to this day. Martha Ani Bedoukian chooses not to identify as white, in an essay that raises the question of whether socially assigned whiteness can be cast aside voluntarily. Today Arabs and most other Middle Easterners are considered nonwhite by antiracists, even though for a long time they identified as white. There is no logical reason outside convention for Armenians to be identified as white if Arabs and Persians are not, though long habit carries weight when it is accompanied by so much social privilege. It crosses a line for most antiracists to call Jews nonwhite, in the same way as it does for people of Irish descent to point out that they too were once considered nonwhite. Yet Kadi includes one poem by a Sephardic Jew, Lilith Finkler, that focuses entirely on the question of whiteness:

In the synagogue of the Ashkenazim,

I ululate at night,

a lunatic from Libya,

One Generation removed.I am the kaddish, the prayer of mourning.

I ache for the Jews of northern Africa,

living among white-skinned peoples.I am the yahrzeit candle

Europe will not light’¦I am the fear of the Arabic

that resides within me.

Of the shrill curses

shouted in desperation.

Of the foods I craved,

the lentil soup and couscous

my mother never cooked.

Of the darker tone of skin,

olive shades,

black eyes and hair.

It was brave of Lilith Finkler to publish this poem in Food for Our Grandmothers as it was brave of Kadi to accept it, and both must surely know it raises more problems than it answers. Kadi’s choices represent a hard line on Israel-Palestine that is necessary in context. It is so in more than one way. To ignore the rights and wrongs of Israel-Palestine’”at least to avoid looking at them in any way that is categorically critical of Zionism’”serves in affect to disappear (and to demonize) real-life Jews by suggesting that if Zionism can be criticized, it means Jews must be evil. That plays directly into the hands of anti-Semites in white-majority countries, whose racism is as easily transferred from Jews to Arabs except under particular circumstances when sympathy for Arabs flatters the white hater of Jews. Instead we need to look hard at the racial politics of anti-anti-Semitism after World War II and how whiteness was implicated in the choice between Zionism and assimilation, as in the forms Zionism took: we must also ask whether it is fair to Jews to rearrange our pre-existing categories of “good guys” to say that some people were always white, and some always not (as in the Cold War era some might always have counted as belonging to the Third World, and some not); so that if the uncritical sympathy some progressives muster for their deserving victims of the day was once given to the wrong “good guys,” it was always wrong and thus didn’t call the politics of sympathy into question. (See, for instance, Karen Brodkin Sacks’ How the Jews Became White Folks.) One of the magnificent things about Food for Our Grandmothers is that it categorically spurns the politics of sympathy, and interrogates their presence in any viable form of antiracism.

At the time of writing, unifying experiences for Middle Easterners in the Americas tended to be understood in terms of politics and ethnicity rather than race in American terms. Kadi made a conscious effort to subvert this trend. But the results in 1994 suggest that while the increased progressive sympathy for Middle Easterners and specifically Muslims (and Arab Muslims) on the grounds of race today is welcome, certainly better than nothing, it distorts the case to use this sympathy as one more certificate of excellence for white progressives: there is a lot more we will need to overcome. This should not be read as a dismissal of race in this context. Race is deeply implicated in American attitudes toward Israel-Palestine (Jews are seen as white, Arabs are not) but the current status of critical race theory in America is that of a strongly American-centered discipline, focusing on the meanings of race in this country. To understand Arab nationalism properly we will have both to understand our own lenses and to put them aside, including but not limited to those of race as we know it in this country. Arabs in the Middle East are scapegoated by Americans according to racial perceptions that do not match those of the Middle East itself and which may represent an erasure of its realities even when American racism toward Arabs is understood in a manner sympathetic to Arabs. In other words we need to be careful that the sympathy does not confirm the misperception.

It is painful to say so, and on one level I hope I am wrong. It would be heartening to imagine that an increased understanding of the social meanings of whiteness and race in America would be enough to bring about a sane foreign policy, and certainly it is hard to see how it could happen without that. But while white Americans who are invested in antiracism might also become invested in treating the Middle Easterners/Arabs/Muslims they know personally with more humanity and humility, it will not be enough to make all the necessary changes in attitudes to foreign policy. There, attitudes and actions which are understood by Arabs as attacks on all Arabs and tolerated by Americans due to racist beliefs are justified and carried out with hatred at times, but also with the conviction that what Arabs most need is to be welcomed into the loving democratic world that will teach them tolerance. American progressivism has more in common with this viewpoint than it dares recognize.

One reason is that American progressivism has for almost fifty years been anti-nationalist, and Middle Eastern nationalism matters to Middle Easterners in ways that Americans can barely understand. The single exception is Zionism, and even that is not a good example given that left-wing American progressives tend to oppose it on grounds of being opposed to nationalism in general, or else to Western imperialism, rather than on the grounds of Arab nationalism on its own terms. Our most lasting encounter with our own racialized social system was in the 1960s, when the nationalists were the white Southerners’”the “bad guys”‘”and the antinationalists the men and women of the civil rights struggle. Today, we still tend to see racial or racialized conflicts in terms of “bad guys” who persist in a misguided nationalism and “good guys,” or at least victims, whose cause can be assimilated into a generalized concern for all who suffer; once the “good” victims make nationalistic claims our lexicon is forced to resort to the canard of “both sides.” However seemingly progressive about race, and despite its real potential to inspire opposition to racism, this viewpoint has the disadvantage of replicating the very attitudes that fueled America’s drive toward the West: a nation that spanned a continent would be big enough to give “all sides” shelter, while this very freedom from the ethnic fortresses of the Old World would in fact be predicated on the destruction of peoples who did not look like “nations” in the same way owing to their race.

It is thus understandable that those Middle Easterners who are still officially white should resent having to pay for their forebears’ decisions in this regard. Martha Ani Bedoukian writes eloquently, and at times arrogantly, about her desire to be rid of a whiteness that imposes an arbitrary separation between her and other Middle Easterners. Her longing is most poignant given the genocide of Armenians in Turkey, in the name of pan-Muslim politics. But Bedoukian’s self-identification as nonwhite rests uneasily alongside her nationalism. Though Armenia receives nowhere near as much American aid as Israel, it receives a lot relative to its size through the efforts of the Armenian diaspora. The West sides with Turkey against Armenia but tolerates aid to Armenia because Armenians are seen as an ethnic rather than a racial or national interest group, thus read as “white.” Nationalism on the part of those inscribed as nonwhite is seen as being a source of dual loyalty whereas nationalism among the white becomes a lobby within the melting pot. One reason why American Zionism caused such rage is that this was one example to the contrary of the arguments raised against Arab identity’”a case of Americans supporting self-determination for a strongly nationalist state, partially, if not entirely, in recognition that its people had needs for self-determination outside of diaspora that had been created through the tragic intervention of history. In a culture where the concept of respect is paramount, it cannot be overemphasized how much the Arabs felt they had been disrespected if any of them were to be forced into diaspora (cut off from the whole) to allow another people to leave theirs. The ethnic kinship between Jews and Arabs did not help. So long as Americans simply do not understand or care to honor the specific cultural needs of Arabs, among them the concept of respect for their sovereignty as Arabs rather than generic inhabitants of the Middle East, we must put aside the “both sides” approach to integrating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with our own culture and acknowledge that the sides are at the very least different. Too much comparison risks eliding a difference in treatment if nothing else, all the more aggravated when and where the concerns have been similar.

Thus the postmodern grid onto which this anthology fit, albeit very roughly, and which a few essays such as Marilynn Rashid’s court, did the Arab world in particular no favors. The theme of deracination with which postmodernism was obsessed could easily be presumed to exist because the Arabs could not bear their own people, especially Arab women, just as some Jews could not exactly be anti-Zionist but suffered from what was done in Zionism’s name’”or else, because they had suffered, however much they might dislike it they could not exactly be anti-Zionist. (Either might have been a rationale for Carolyn Forché’s having placed Abba Kovner alongside Mahmoud Darwish’”whom she has translated’”in her essential anthology Against Forgetting; to take only one wincing example of this phenomenon.) Packaging aside, Kadi’s collection was valuable for all the contrary evidence it presented: it showed over and over that these women and their forebears were not in the Americas due to the oppressiveness of Arab society but because of a home environment made intolerable by foreign powers. One poem by Laila Halaby combines this theme with almost every other one touched on in this collection:

Two Women Drinking Coffee

They sit in jeans and drink their coffee, black

As kohel on their eyes. They pour their tales

Of broken romance through a sieve: the words,

While cardamom in flavor, are in English.

Today they’ve met outside a café;

Their work is done and each is going home.

It’s here they punctuate each other’s day

With stories, lively jokes, and cigarettes.

The mood is soft, the laughter not so strong.

The talk is dominated by their thoughts

Of home, to which there’s no return: like love

That’s lost and leaves a stinging sadness there

To bite the heart without a kind of warning.

The one who’s lost most recently then sighs.

Her hands are silent, her head turned away

As she speaks in words with orange blossom scent:

The angel I believed was always here

Has flown to heaven and I now must cope

Alone with love that’s in a different tongue

I understand too well to misinterpret.

Among other things, Halaby’s poem describes a dimension of Arab culture occupied by relationships between women as friends, not just grandmothers, mothers, and daughters. The “coffee,” “cardamom” and “orange blossom” belong to the two women together rather than an objectifying gaze. Sadly, that objectifying gaze can also be feminist. Therese Saliba points out that “the dominant discourse’s emphasis on the Arab woman’s body and her position within an alleged despotic family structure allows external forces of racism and imperialism to continue unquestioned,” and in one of the strongest political essays, Carol Haddad tells how her and other Arab feminists’ opposition to the Israeli invasion of Lebanon was undermined by white feminists’”some Jewish, but by no means all.

In some ways the title is a misnomer. The women in the collection are all exiles from their grandmother’s worlds. Though there is no bald rejection of this world, there is a clear sense that it is never to be recovered, and the grandmother herself appears seldom, despite Kadi’s assurance that she is everywhere. One keystone essay is Therese Saliba’s “Sittee (or Phantom Appearances of a Lebanese Grandmother),” bordering on fantasy with its evocations of the grandmother’s presence (like the ghostly female in Emile Habiby’s Saraya, the Ogre’s Daughter). Sitti appeared so often in the submissions Kadi collected that the title was obvious to her even though the subtitle locating the collection in North America was not. The disparity sums up that between a world in which there are clear female figures of power in the sittis, and a world in which female power is propagandized as being there for the asking but is often not there in practice. If there is relatively little about specific feminist issues apart from Western objectification, it may be less because Middle Eastern culture is antifeminist and more because the gulf between sitti‘s world and her Americanized granddaughter’s is widened by dislocation with an outside cause. It is interesting that the closest approach to original folkways and folklore is made by lesbian writers such as Kadi and Saliba. The other Armenian voice in the collection, Zabelle, begins to introduce folklore by telling the story of the magical horse Lulizar. Lulizar delivers a lost princess back to the king of Armenia together with a young village woman dressed in boys’ clothes:

Complications arise on the wedding night, when the princess, who had after all been living with the young woman prior to her marriage, “discovers” the sex of her new spouse. From then on the princess plots to get rid of her by having the young woman sent on various dangerous quests, but each time the magical Lulizar helps her to succeed. Finally she is sent to recover a rosary from the “mother of the devs,” who curses the unseen thief with an instant change of sex’”a solution which satisfies the princess. ‘¨

I believe it is time for a new telling of the story, one in which the women have names, the mother of the devs cures the princess of her homophobia, and Lulizar receives the freedom that is her just reward. Then everyone can live happily ever after.

We don’t know what would be different in a collection of this nature if it was published today, because there hasn’t been another quite like it. What would surely remain and have only grown in strength would be the psychology of self-division, though it is no longer fashionable to speak in terms of fragmentation and contradictory oppressions. Today the pendulum on the left has perhaps shifted again to finding a “magic bullet.” One may thus be worried by the example of Israel-Palestine, when a person oppressed in one context can be the brutal oppressor of another in another context, and none of the explanations of intersecting oppression appear to fit all the facts. It is not clear if there is a “magic bullet” that can be aimed at the origins of all oppression, or if, as people of good will, we will turn out to have more in common than not. But in the face of the kind of hatred given expression by Elizabeth Moon, it is very clear that we dare not tolerate a world where in the name of ending one hatred, we underwrite others. Whether this will mean an end to “passing” or whether the passing will continue is yet to be seen.

This is a powerful set of writings. The objective tone I have taken in writing this review risks making it invisible that for about forty-eight hours after reading it, I was unable to function, and shelved many pressing obligations to write several pages of personal reflection on my own experience as a woman in an adopted Middle Eastern culture. I decided, eventually, not to include these reflections, influenced by Therese Saliba’s warnings about white women in the culture replacing Arabs and others to whom it is in some way native as we share our experiences. My experiences are not irrelevant, but they belong elsewhere. This is true for more than one reason. Despite the folksy-sounding title and section headings, Food for Our Grandmothers is not about folkways. But it is also not about deracination for its own sake. In “Five Steps to Creating Culture,” for all its partially simplistic approach to what “culture” is about, Joanna Kadi makes some outstanding points:

When I pondered my grandmothers’ activities I realized we have not noticed them. They are not what springs to mind when we think of cultural achievements. There may be several reasons for this: let me name two that I think are important. First, our community has not always noticed or affirmed women and the things we do. Second, these parts of our culture are so common and so present that we tend to overlook them. When you watch someone make laban once a week for years and years, you do not notice the importance of what they are doing.

I did not sit in the kitchen smelling warm milk and think to myself: My grandmother is engaged as a cultural worker. But that is what she was’¦ One point of my confusion had to do with what it meant to have culture. Growing up, my only understanding of culture was what white, middle- and upper-class people achieved and did. I could not translate that understanding to my identity as Arab and as working-class. So, although my family listened to Arab music, danced Arab folk dances, and ate Arab food, I did not perceive any of this as culture. Perhaps if we had not been so isolated from a larger Arab community things would have been different. But as it was, the people around us, and society generally, perceived our music and our food on good days as a series of weird, isolated, and exotic behaviors that for some reason my family engaged in. On bad days they perceived it as disgusting as well as weird.

It is only now with the benefit of hindsight that I understand I grew up surrounded by Arab culture. It is only now that I understand what happened in my grandmother’s kitchen’¦ Gram is making laban. As is always the case when she cooks and bakes, there is no recipe. No directions, no reminders. Still, she knows exactly what to do [my emphasis]’¦ I want to create things that allow my loved ones not only to survive but to flourish. But there is a big, big difference between my grandmother and I’¦ She is secure in the knowledge of what to do. I am not. I am foraging for a recipe, a tradition, one that originated in the east and will serve me well in the west.

This knowledge was not written down and the creation of the need for it to be written down is itself political: the sittis are not in the villages where many of them expected to live their whole lives. Understanding this, one has a better sense of the tragedy represented in Emile Habiby’s masterpiece Saraya, the Ogre’s Daughter, where Habiby’s narrator has made himself a “book” in the same way as people in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 103 became “books,” memorizing as much of Palestinian folklore as he can and situating it in the landscape of historic Palestine. In this he is doing what his forebears did: the difference is that he has to do it on purpose, and also write it down. Martha Gellhorn Sa’adah writes: “This is the way a generation ends. By writing a recipe down.”

One can hope that Sa’adah is wrong about this and Kadi is right, and still fear it is the other way around. Either way, Kadi’s collection must still be taken very seriously indeed.