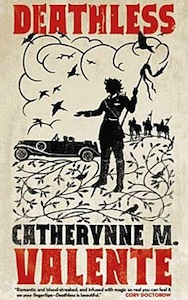

Deathless

Deathless

by Catherynne M. Valente

Tor Books, 2011

Reviewed by Sofia Samatar

A woman takes a man downstairs, into her basement. She commands him to stand against the wall and ties his hands to a meat-hook. She kisses him, strikes him, gloats over him. The man closes his eyes in ecstasy. Does he want to get away?

Yes and no.

Yes, he wants to get away; but only because the desire to escape generates pleasure, and pleasure, of course, is the reason the man is tied up in the first place. This tension between desire and restraint, between the urge to break free and the pleasure of being trapped, creates the energy of Catherynne M. Valente’s Deathless.

Deathless is Valente’s first novel set in Russia (the companion volume, Matryoshka, is forthcoming in 2015). Time in Deathless is double: there is the time of the twentieth century, approximately from the Russian Revolution to the Siege of Leningrad during World War II; and there is the time of the fairy tale, which is always.

The central fairy tale at work here is the story of Koschei the Deathless, a being whose immortality is guaranteed because his death is elaborately hidden. Like many immortals, Koschei is a demon, and he has a demon’s attributes: beauty touched with a hint of repulsiveness, passion that veers toward cruelty. When Marya Morevna, a human girl, marries him, two questions arise: first, if a human loves a demon enough, can she become a demon too? And second, can a familiar tale grow a different ending?

The answer to both of these questions is: yes and no. Marya’s struggle with the first question really starts before her marriage, when she’s a young girl dazzled by Pushkin and tormented by other children, who call her “crazy” (p. 27). Marya’s “craziness” is vision: she sees magic. She knows that her sisters’ husbands are birds in disguise, and in a particularly delightful episode, she meets the dwarfish domoviye who live in her house, and attends a meeting of their boisterous goblin workers’ collective. Marya’s sensitivity to this hidden world makes her an outcast: “She was a person, but she was not one of the People” (p. 28). When she marries Koschei and moves to his land of Buyan, the Country of Life, she seeks not just love, not even immortality, but community.

Marya makes a good demon, and she makes good demon friends. But the second question, the question of the inevitability of fairy tales, comes to haunt her. As she discovers some of Koschei’s secrets, she finds that being a demon means living out demon history, which is a history of repetition. “We obsess,” Marya is informed by the most famous character of Slavic folklore, a wonderfully bawdy and sadistic old woman who calls herself Chairman Yaga: “It’s our nature. We turn on a track, around and around; we march in step; we act out the same tales, over and over, the same sets of motions’¦ We like patterns. They’re comforting” (p. 110).

Patterns may be comforting to a demon, but Marya is stuck in a tale at the end of which she is supposed to abandon Koschei. She is also supposed to attempt his murder. Her efforts to escape the pattern initiate a new phase in the war between Koschei, the Tsar of Life, and his brother, the Tsar of Death. This cosmic war is juxtaposed with the violent history of twentieth-century Russia, in manner that examines the question of power, an issue that also takes shape in the novel as the central question of marriage: “who is to rule” (p. 58).

Deathless keeps a lot of elements in play: there’s a double history, a quest, and a variety of vivid characters and landscapes. There’s also a powerful commentary on marriage, in which the world of married partners figures as a kind of Buyan, a Country of Life, necessarily a little bit demonic: “A marriage is a private thing. It has its own wild laws, and secret histories, and savage acts, and what passes between married people is incomprehensible to outsiders” (p. 215-16). The trickiest part of all this is not the movement back and forth between fairy tale and history (though that is hard enough to pull off), but the movement between the large, collective history of Russia and the private, individual history of Marya Morevna’s marriage. There’s a risk, either that the suffering of an immense number of people will appear less important than a single woman’s relationship with her husband, or that Deathless will come off sounding like the punch line to a feeble joke that goes: “Why is Stalinism like a bad marriage?”

Realism saves Deathless from the former fate, and fantasy saves it from the latter. By “realism” here I mean all the extraneous stuff that literature uses to imitate life: the sneezes and make-up and kettles and subplots and minor characters that differentiate the novel from the fairy tale. A good deal happens outside the lines of Marya and Koschei’s story: Marya becomes a soldier, she loses friends to war, and she is forced to admit her own role in the oppression of faceless others, whose right to be heroines is equal to her own. By straying off the strict path of the fairy tale, and addressing the creation of an individual heroine as an ethical problem, Deathless avoids turning its setting into mere window dressing. As for the other risk–the risk that Deathless will be read as pure allegory–fantasy comes to the rescue, for fantasy can say “yes” and “no” in the same breath. Yes, Marya’s sisters marry birds; and no, they don’t, because they marry men. Yes, Stalin is a little village boy who stomps on flowers. And no, he isn’t. He can only appear as such in a country where there is no death–and that country, the novel insists, is not ours.

Above all, Deathless is about the magic of fairy tales, and the narrative patterns that shape us even as we try to change them. A story can save you, but it can also trick you. A story can ruin your life, yet remain as beloved and compelling as a certain meat-hook in the basement. Like Marya’s secret ability to see magic, your story may tell you: “I am your husband and I can destroy you” (p. 28). You may need to get away from that story. You may need to tear the ropes, get out of the basement, break the pattern.

Do you want to?