When the birds came, we novices fed them bread from the last night's meal. The sunlight shone on the gloss of their purple wings as they feasted and filled the courtyard with their cries. Afterwards, they shat copiously upon the temple stairway, and I and the other youngest novices were made to scrub it off late into the night.

When the birds came, we novices fed them bread from the last night's meal. The sunlight shone on the gloss of their purple wings as they feasted and filled the courtyard with their cries. Afterwards, they shat copiously upon the temple stairway, and I and the other youngest novices were made to scrub it off late into the night.

The next day, the birds returned, blotting the sun from the sky as they descended upon the temple. We brought them bread again, this time newly baked and warm in the gathered folds of our course blue habits. We cast the birds large pieces torn from the loaves, but they refused it.

So from the cool shadows of the kitchen, we fetched oranges which bore only a trace of white lacework mold upon their skins. They had been carried by mule from the south, picked by brothers of our creed. We brought this fruit to the birds, our feet murmuring on the stone floor of the colonnade. At this offering, the birds lifted and dissipated like a fog, beating their wings, filling the air with chirruped discontent. The mother priest in her saffron robe came to us and watched the birds with awe. She told us, these are a sending from our Sovereign of Heaven.

So she sent us to the orchard for plums, sweet and meticulously tended. Our voices were tense between the branches as our trembling fingers pulled the fruit free.

Keeping our distance, we cast the plums upon the marble steps to the birds. They refused them, and the fruit lay languishing in the sun, sticky upon the marble stairs, bleeding out their juices, drawing flies. And I began to understand that the birds' shit upon the marble was preferable to the stairs' white gleam.

Next twilight, we brought out ham’”we had slaughtered our only pig for them. I with the others placed a meat-laden platter on the topmost stair and watched as the birds drew near, a silent black cloud. Their wings whispered an uncanny incantation.

Hope nearly left me then: the birds swarmed over the meat, raising their maddening cry.

But they did not eat.

Our mother priest had told us what we must offer if the birds of the Sovereign of Heaven were not appeased. The other novices began to weep, but I’”I could only watch the birds throng about the platter. Even with their cacophonous hunger, not a one took a bite of meat.

I was the first to lie upon the cool stone steps; other novices followed. If the birds would not relent, hope would have to lie in the boon afforded by yielding.

The birds first descended upon those of us prostrate, our blue robes like pools between the columns. My own cries and the other novices' mingled with the birds' shrieking as they pecked and tore our flesh.

The birds ate us through the night and into the next day. A crowd gathered, I know not when. With a remaining eye I could see the people assembled about the temple steps. Soon that eye was gone, and I could only hear the crowd's murmurs, the ever-burgeoning flutter of wings, and the chorus of cries, human and bird, indistinguishable. Then my hearing was taken, too, in the bright pinch of their beaks and claws.

Before the sun set, there was nothing left of what I or any of us had been. Not a length of bone nor a scrap of pluck remained. The marble stairway gleamed white. Our empty habits were patches of sky beneath the colonnade. So I saw from the column capitals.

Then I drew up with the other birds, all purple feather and beak and iridescent eye, borne up on a beatific wind. On new wings I went with them towards a new temple, a cry at my throat and a wild, divine hunger at my belly.

Darja Malcolm-Clarke attended Clarion West in 2004. Her fiction appears in the anthology TEL: Stories and on the webzine Three-Lobed Burning Eye, and she has poetry forthcoming in Dreams and Nightmares and Mythic Delirium. She has Masters degrees in Folklore and in English from Indiana University and, having little use for sanity, is pursuing a doctorate in the latter. She is an articles editor at Strange Horizons, and her intermittent and somewhat manic blog can be found here.

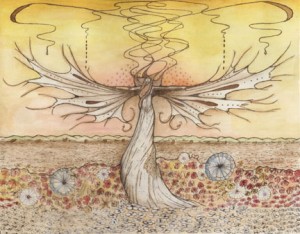

Image © Michael “Warble” Finucane, Wings Are Spread

The Art of Warble is base upon the designs and illustrative art of the 19th century. By infusing the fairy lore of Warble's childhood into the developed technique of an adult artist, his art has become popular in the fairy art genre. In being able to keep “the child's mind” of early youth, Warble has been able to bring this imaginative 'interior' perspective out onto paper as an artistically trained adult. Although Warble paints other various fantasy based paintings, it is the fairy art that truly makes magic in his painting ideology. Without hope or belief in the fairy lore of the western mythos, faith cannot be achieved to bring this ancient heritage into the modern 21st century. In this manner, Warble executes love and hope within the fantasy and fairy art in which he has become renowned for in the art world.